How do you spend over £5m piling up clay to reopen a half-mile length of canal? It turns out there’s rather more involved in the next phase of the Chesterfield Canal’s restoration, as Martin Ludgate finds out when he visits…

“Piling up a load of clay”

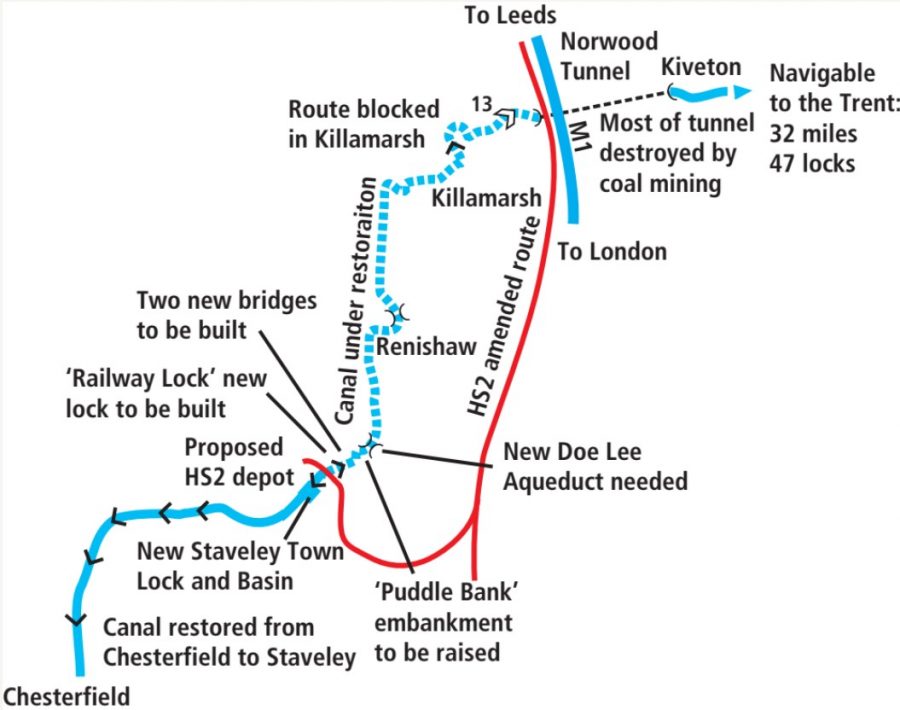

“You’d think just piling a load of clay up would be nice and easy”, says George Rogers, engineering graduate, Waterway Recovery Group canal restoration volunteer, and for the last four years the full-time professional project manager for the Chesterfield Canal Trust. They’re working to restore the remaining ‘missing link’ eight-mile length of unnavigable canal from Staveley to the start of the main navigable section at Kiveton – from where the canal’s open for 32 miles all the way to the Trent: see our cruise guide.

We’re at Staveley, near the eastern end of the isolated restored length of canal from there to Chesterfield, so that George can show us why the next phase of restoration, where the principal task could indeed be described as “piling up a load of clay”, is going to be anything but easy or cheap. In fact it’s going to be so expensive that despite the very welcome recent confirmation of over £5m of funding from the Towns fund (see news pages), the available resources will only pay for something like the first half of the work to complete the length of canal within Staveley town’s boundaries.

The new Staveley Town Lock looking from Staveley Town Basin towards the section to be restored

Staveley’s new canal and basin

We start at Staveley Waterside, the renamed Staveley Town Basin, created more than a decade ago to create a focus for the restored canal in the town. It’s now finally (after delays following on from the economic downturn of the late 2000s) set to be surrounded by developments of small businesses, retail, cafes and housing, and hopefully achieve this role. Heading eastwards, the canal leaves the basin via the new Staveley Town Lock, built largely by CCT volunteers. This was necessary to lower the canal so that it could pass under a bridge carrying an out-of-use (but not officially abandoned) freight railway line, in a former coal mining area where subsidence has badly affected ground levels. The idea was that a second new lock (known as Railway Lock) would be built on the far side of the railway bridge, to bring the canal back to the original level.

Beyond Staveley Town Lock, we follow the lowered length of canal as it runs past a complex overflow weir structure and under two new road bridges before coming to an abrupt end just after it passes through the remains of the railway bridge, now missing its deck. This is where the section to be funded by the Towns Fund grant will start – and also where the impact of the HS2 railway on the canal restoration is still being felt – so let’s pause our walk-through to delve a little deeper into these two issues.

The canal currently comes to an end at the remains of the old railway bridge

HS2’s impact on the canal restoration

Dealing first with HS2, when the high speed railway’s proposed route was first announced a decade ago, it looked set to obliterate a whole swathe of the Chesterfield Canal’s route. It would lay waste to completed restoration work in the Renishaw area, making future restoration very difficult. But a re-think of the way that the line would serve Sheffield led to a change of route, almost entirely avoiding the canal – except for the need for a new railway infrastructure maintenance depot which would be at the end of a siding leading to Staveley. And that siding would cross the canal at the site of the out-of-use railway bridge mentioned above. But the plans weren’t clear on what height it would cross at: in order to be sure that the canal would get under the railway siding, plans had to be made to lower the canal even further via a second new lock.

And despite this north eastern section of HS2 having been shelved in early 2022, it hasn’t officially been permanently abandoned. So the canal restoration needs to make provision for the possibility of this second new lock being needed to get it under the railway, followed by a single deep lock to bring it back to the original level. But given that the railway might never be built, and even it is, it might be built at such a height that the second extra lock isn’t needed, it would be wasteful to spend money on something that might never be needed. So for now, the restoration will proceed on the basis that the canal will be able to pass through on the current level, but will be designed in such a way that it can be modified to cope with HS2 if necessary.

Finding the cash

Turning now to the funding of the next section: when the Canal Trust first looked at bidding to the Government’s Towns Fund, it seemed that a grant of around £8m might pay to complete the entire remaining 1½-mile length that’s in Staveley Town’s area (and therefore eligible for the funding), so it put in an expression of interest for that amount. The work would consist of the new Railway Lock already mentioned, four new bridges, a lot of channel reconstruction, and most importantly the raising of the ‘Puddle Bank’. This is an impressively large clay embankment across the Doe Lea Valley – quite a major feat for such an early canal – which has suffered badly from subsidence, erosion and the removal of the section which crossed the river. So restoration requires a huge amount of extra clay, both on the embankment itself and to raise the badly subsided lengths of canal approaching it from either direction. And that’s the “piling up a load of clay” that George referred to earlier.

The one problem that the Trust doesn’t have is sourcing the clay. Very conveniently a local landowner still has a large stockpile of clay originally intended for a brickworks which closed down some years ago, and is kindly donating all 160,000 cubic metres to the Trust.

Meanwhile, back came the Towns Fund with an offer of £4m, half of what CCT had asked for. The Trust was concerned that even if the whole length couldn’t be restored, it was important to carry out works to some kind of intermediate level of ‘completeness’ – and that a £4m grant wouldn’t do this in any meaningful way. So it came up with a plan to complete the earthworks and aqueduct and rewater the whole length, but leave the lock and three of the bridges until later – and a revised bid for £5.6m. Unfortunately rapidly rising prices coupled with a shortfall in the Government’s Towns Fund grant to Staveley (meaning that there was only £5.3m available) led to a funding gap that was too big to fill, so CCT had to have another re-think. It decided that instead of rewatering the whole section, it would take a different approach and go for complete restoration to navigation for as far as it could from the Staveley end of the section. And so it came up with a plan to restore the first half mile – and that’s what the Towns Fund has now agreed to support.

What the money will pay for

That sounds like a lot of money for a very short length, but as we continue eastward along the route, we can see where a great deal of it will go. Following a footpath up a ramp alongside the old railway, we reach a junction where a sign indicates we have met the Trans Pennine Trail. This is a long-distance footpath and cycleway based on another old railway, part of the former Great Central line. Where it used to cross the canal there is now a large gap, the bridge having been demolished in the 1970s – and a new bridge spanning something like 120ft across the canal will be one of the first main construction works forming part of the canal restoration, scheduled for 2023.

A new bridge will carry the Trans-Pennine Trail over the canal here

It’s important that his job is done first, because building the bridge will allow the Trail to be diverted from its current route which runs down a ramp and across the canal bed. And that, in turn, will allow the ramp to be demolished, and the new Railway Lock to be built in its place in 2024-25. George points to roughly where the lock will be, but it’s quite hard to envisage.

Returning to the bank of the canal (although the channel is filled in, and there’s little to see of it apart from a line of coping stones where yet another old railway bridge once stood), we follow the towpath eastwards. A farm track and a couple of gates mark where a new farm access bridge will need to be built over the canal – also planned for 2024-25.

It’s possible to make out (at least when George points it out) where the canal widened into a small basin and junction with an arm: this was where an archaeological dig a few years ago unearthed the remains of three historic boats, and it’s where a local landowner has plans for a small marina or mooring basin.

Beyond, as we continue along the towpath with the canal visible alongside (improved by some heavy vegetation clearance by CCT’s volunteers), it’s obvious that we’re entering an area badly impacted by mining subsidence, as it drops away by at least 10ft over the next couple of hundred yards. I’m beginning to see where some of the 160,000 cubic metres of clay might be needed! But I’m also wondering if there isn’t an easier way…

“So why not just avoid all these earthworks by simply missing out the extra lock, rebuilding the whole length of canal at a lower level, and adding a new lock further east when you’ve got past the subsidence?” I ask.

George explains that unfortunately, close to the site for the new Trans Pennine Trail bridge, two very large sewers pass under the canal at only just below bed level. Lowering them would cost millions (it might well involve a new pumping station), and would easily outweigh the cost of building the subsided length of the canal back up to its original level.

As we continue, the canal undulates up and down (clearly the subsidence was inconsistent along the length) as it approaches a sharp right bend. Here, rather in the middle of nowhere, is the official limit of the half-mile length which will be returned to navigable standard by 2026 under the funded works.

To be restored by 2026: the line of the canal and towpath snaking away into the distance

And then what?

But we don’t stop there – and neither will the restoration work. Although this has to be the stated end of work in the interest of what George refers to as the “robustness” of the funding bid, he’s hopeful that savings can be made which will enable it to continue further.

And while this work is under way, CCT will be targeting any available sources of cash (such as the new Government Shared Prosperity Fund) with a view to raising the funds for the remainder of the Staveley section. As we approach the Puddle Bank we can see where this (and the rest of the 160,000 cubic metres of clay) will be spent. As the land drops away the embankment rises to around 25ft high, but it will need to be anything up to another 10ft higher to maintain the level. There’s one enormous gap in it where a section has been dug away, and an even bigger one where the river passes through and a major new aqueduct is needed. And just to make it more interesting, the site’s overlooked by high voltage power cables, precluding the use of a large crane to install it.

The next phase: site for the new Doe Lea Aqueduct

This is where we turn round – but it’s only about another mile beyond here (plus two more rebuilt bridges) to the end of the Staveley town section. And from there on, the much more straightforward length through Renishaw follows. Then it’s down to the final four miles – and those will be difficult miles, with the twin problems of the built-on section in Killamarsh requiring a major diversion with new locks, and what to do about the 1¾-mile Norwood Tunnel, most of it destroyed by coal mining.

However with discussions under way with Highways England regarding the tunnel (it’s crossed by the M1, making it eligible for the same new roads remediation funding which recently paid for the Cotswold Canals to cross the A38 roundabout near Stonehouse in Gloucestershire), and with the first big step towards rebuilding the Puddle Bank now under way, George reckons it’s something like a case of “One down, two to go” as regards dealing with the major obstructions.

He admits that CCT’s target set a few years back of reopening the canal by its 250th anniversary in 2028 was “optimistic”, but he believes that it’s succeeded in galvanizing effort to get the restoration back on track after the HS2 blight and heading towards complete reopening. And it starts with piling up a load of clay…

To find out more about the Chesterfield Canal restoration, to join the Canal Trust or to volunteer to help with the restoration, click here