Our canal boater’s cruise guide to the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal takes you from the outskirts of Gloucester to Sharpness Docks…

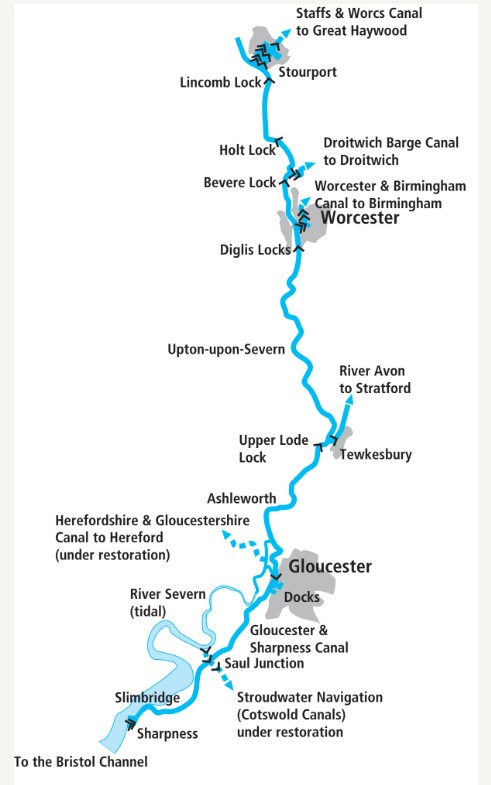

In our Cruise Guide to the River Severn we mentioned that the non-tidal reaches of the Severn could be a very unreliable navigation in the past – hence the eventual construction of the locks, and the decline of navigation above Stourport. The same was true of the lower tidal reaches, but for different reasons – and the way of dealing with them was different too: a canal was built to bypass the entire section of the river.

The Severn downstream of Gloucester suffered from shifting sands, a huge tidal range, fast tides (made more dangerous by the famous Severn Bore, a tidal wave which marked the arrival of the biggest tides), and a lack of depth which meant that larger seagoing craft could only use it around spring tides when it was at its most hazardous.

In 1793 the Gloucester & Berkeley Ship Canal was authorised to bypass the trickiest length; in the event, shortage of funds meant that it took until 1827 before it was finished, its length was reduced so that it ended at Sharpness rather than Berkeley (hence the name that it is now known by), and it took decades to pay off its debts.

But it succeeded in avoiding the hazards of the tidal river, it led to the development of Gloucester docks (which form its northernmost length), and having been built to take sizeable ships it was for a time the widest and deepest canal in the world.

Feeling thirsty? See our top ten pubs on the River Severn and Gloucester & Sharpness Canal here

Gloucester Docks are surrounded by historic warehouses, with some interesting craft moored

Busy with shipping and barges until well into the mid-20th century, the docks then declined with the transfer of much of the busy oil and petrol traffic to pipelines, and the last tanker trade ended in 1985, leaving just the passing grain barges for Tewkesbury until the 1990s, plus occasional one-off ship passages since then. But the canal remains open, Sharpness Docks are still in commercial operation for seagoing traffic, and at the other end of the canal the historic warehouses at Gloucester Docks have found new uses including the National Waterways Museum in Llanthony Warehouse.

The entrance lock from the Severn leads straight into those docks, with a fine view of the historic warehouses on all sides, historic vessels moored up, and perhaps if you’re lucky a visiting tall ship. Immediately on your left are pontoon visitor moorings for exploring the docks, the city and all its attractions, while there are permanent moorings in a second basin (Victoria Dock) connected by an arm, also on the left.

Built for sailing ships of the early 19th century ago, the Gloucester & Sharpness Canal had no restrictions on headroom, with all bridges capable of opening to allow ships to pass – and that’s still the same today. So at the far end of the main basin there’s a liftbridge that will be opened for you by the keeper (subject to you arriving during opening hours – see Boaters’ Notes) which leads into the canal ‘proper’.

At this point I feel I should make an apology. When I first visited the Gloucester & Sharpness Canal 30 years ago, I imagined that as a canal built along the floodplain of a large river, designed to take ships of 200 years ago, it would be very straight, wide, deep, flat, and – frankly – dull. Well, having cruised it I could confirm that it was indeed flat (no locks other than those to connect to the Severn at each end), and as you’d expect it’s certainly wide and deep. But straight and dull? It’s true that the canal sets off on straight course heading south westwards through Gloucester’s outskirts, but there are a couple of interesting new bridges to enliven it.

As I mentioned, there are still no limits on boat headroom, so even modern bridges constructed over the last 20 years as part of a major road improvement scheme have to be capable of opening, although there’s plenty of headroom under them for canal craft so you won’t be holding up Gloucester’s traffic.

Two Mile Bend used to be quite a challenge for ships (if not for narrowboats), but the construction of one of these new bridges was accompanied by the easing of the curve. In between the new bridges are more traditional examples – mostly power operated these days by keepers, but often still accompanied by the cute ‘classical’ bridge-keepers’ houses, complete with little columns supporting a pediment. Most of them will need to be swung open for canal craft, although a few are high enough to pass under – but don’t disobey the ‘traffic lights’ protecting them (I got shouted at and my details taken down on my 1990 trip!)

At Saul Junction the soon-to-be-restored Stroudwater Navigation crosses the canal

Following another sharp bend (by ship canal standards) the canal leaves Gloucester’s outskirts and passes through open countryside (still punctuated by swingbridges) to reach Saul Junction. This was once a four-way ‘level crossing’ of waterways, with G&S cutting through the earlier Stroudwater Canal on its way from the Severn at Framilode to Stroud, where it met the Thames & Severn Canal.

Today the length from Saul Junction to Framilode (largely superseded once the G&S opened) is long abandoned but walkable, with the junction lock ‘cosmetically restored’ including interesting lock paddle gear reminiscent of some of some Leeds & Liverpool gear. But in the opposite direction, towards Stroud, it’s scheduled for complete restoration and reopening between now and 2024 under the Lottery-supported Cotswold Canals Connected project, as an important step towards reopening through to the Thames. You can read about it in our Restoration Feature from a little while ago, but the good news is that since that was written, the funding has been confirmed, work has started, and the new railway bridge needed to cross the restored canal at Stonehouse has been built over Christmas and New Year 2021-22.

In the meantime, Stroud is an attractive location with swing footbridge and junction cottage, and a useful boating centre with adjacent marina and boatyard.

Frampton-on-Severn follows closely: it’s notable for (reputedly) the longest village green in England, plus a couple of handy pubs within walking distance (unlike the Severn, canalside hostelries are few on the canal) and a shop. The amusingly-named Splatt Bridge (it takes its name from the adjacent small settlement of The Splatt – but where does that in turn get its name from?) is still manually operated by the keeper winding a large handle.

Splatt Bridge: still manually operated

Another rural length leads through flat countryside – but with glimpses of hills in the distance on both sides – and past the Slimbridge Wildfowl and Wetland Trust’s well-known reserve a little way to the west of the canal. There are glimpses of the Severn estuary as the canal approaches Purton, winding its way around higher ground and passing a couple more swingbridges. For the final mile and a half, the canal runs along the edge of the estuary, and this is where its bank has been protected over the years by the famous ‘Purton Hulks’.

Passing Patch Bridge which provides access to Slimbridge Reserve

A curious circular stone tower on the west bank of the canal is a remnant of the swinging span over the canal of the ill-fated old Severn Bridge, a metal railway viaduct which crossed the estuary until 1960. Its demise was the result of a collision in thick fog and strong tidal currents between two loaded tanker barges; their skippers lost control and the barges were swept into the bridge, demolishing one pillar, bringing down the two adjacent spans and catching fire. Five men lost their lives in the disaster, and the rest of the bridge was subsequently demolished. On the towpath, it’s commemorated by a plaque and a model of the swinging span.

Approaching the two swingbridges at Purton

Another half mile leads to Sharpness and to a split in the canal: to the right, the original line, leading to the remains of the old entrance lock into the Severn, is now a marina and visitor moorings; while to the left, the navigation leads under two swingbridges and through Sharpness Docks to the modern ship-sized entrance lock and the Severn estuary. If you’re planning on heading out into the estuary to make the adventurous trip to Avonmouth and the Bristol Avon, this is your route onward. If you aren’t, bear in mind that this is a working port, and keep clear of it.

Site of the canal span of the ill-fated Severn Railway Bridge

Sharpness Docks are an interesting (if slightly bleak in places) area to see from the places that are publicly accessible (which include a walkway across the gates of the ship lock), with warehouses, old railway tracks, a small railway preservation group, the entrance basin, and the views out over the estuary. When we were there, the assorted craft at the boatyard by the lock included narrowboats and broadbeams, a cruiser so large that it had a helicopter deck (with helicopter), something that looked like a Mersey ferry, and a lightship! It’s not your typical boatyard, but then the G&S (and for that matter the Severn) isn’t your typical waterway. I hope I’ve shown that my initial expectation that it would be “dull” was well wide of the mark.

The final length leading through Sharpness Docks

Image(s) provided by:

Martin Ludgate