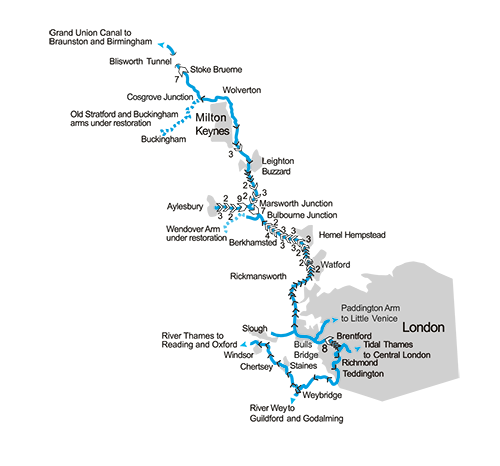

Two contrasting waterways – the Grand Union Canal, backbone of the southern canal network and the royal River Thames – take us on the second part of our journey around the great southern waterways circuit.

Words and pictures by Martin Ludgate

The Canal Museum at Stoke Bruerne in Northamptonshire was where we ended part one of our cruise round the great 246-mile lock circuit of the southern waterways, made up of parts of the Grand Union Canal, the River Thames, and the Oxford Canal. So, we’ll begin part two by resuming our journey south along the Grand Union main line, with the flight of seven broad Stoke Bruerne Locks continuing the descent from the summit level which began back at Buckby.

The Canal Museum at Stoke Bruerne in Northamptonshire was where we ended part one of our cruise round the great 246-mile lock circuit of the southern waterways, made up of parts of the Grand Union Canal, the River Thames, and the Oxford Canal. So, we’ll begin part two by resuming our journey south along the Grand Union main line, with the flight of seven broad Stoke Bruerne Locks continuing the descent from the summit level which began back at Buckby.

They’re an interesting flight to the waterways’ enthusiast. In the 1830s, the canal was busy enough that the locks were duplicated, with two widebeam locks side-by-side; the second locks lasted no more than 30 years, but traces of them remain, and in the case of the top lock, the old chamber has been re-excavated and modified into an outdoor exhibit of the museum, with an unusual set of Montgomery Canal iron bottom gates and paddle gear installed. Also visible as you continue down the flight, leaving the village behind, are former ‘side ponds’, water-saving chambers alongside the locks and connected to them by side paddles, as a way of re-using part of each lockful of water. They were added later in the 19th century, and remained in use until the mid-20th century – and several are now nature reserves.

Below the bottom lock, look out for where the towpath is carried on several sets of low arches spread over the next mile or two: these aren’t just historical relics, they’re where the excess waters of the River Tove (normally a modest sized stream which passes under the canal in a culvert) can be carried across the canal in times of flood. This can create a significant current in the canal, as well as raising the level and flooding the moorings below the bottom lock, so it’s worth being aware of.

A quiet rural length of canal leads to Cosgrove, with its unusual decorative Solomon’s Bridge, and a tiny ‘horse tunnel’ carrying a footpath under the canal (and providing access from the moorings to the village and pub). It’s where the Old Stratford and Buckingham line of the canal used to branch off, and thanks to the efforts of the Buckingham Canal Society the first section of this former branch has been restored, with further work and plans in progress – see our article in the December 2024 issue.

A single lock lowers the canal to its lowest level (What’s the opposite of a ‘summit level’? I’ve heard it called a ‘trough pound’ by waterways staff) before it begins climbing again towards the Chilterns. But that’s some distance off: first we’ve got the aqueduct at Cosgrove over the Great Ouse, then the former railway town and useful shopping stop of Wolverton, then a brief rural interlude before the start of Milton Keynes.

Fenny Stratford Lock, notable for its very shallow rise and its swingbridge

Britain’s largest new town may have been the target for some sniping over the years, but it certainly makes the most of its canal, with a strip of parkland with footpaths and cycleways following the waterway for the entire seven or eight miles through its largely residential areas. Look out for two canal connections, one long since lost (the start of the former Newport Pagnell Arm is marked by a short section of piling and commemorative wall plaque by Bridge 77) and one yet to be built (the junction for the proposed Bedford to Milton Keynes Waterway and the first few yards of the new route were built at the same time as the new Campbell Wharf Marina with its striking new towpath bridge nearby).

Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park

A mile and a half walk from the canal in Fenny Stratford (or take the LOOP bus from Bridge 90C in Milton Keynes to Bletchley) brings you to the former country house estate and surrounding collection of huts which formed the nerve centre of Second World War codebreaking and the birthplace of computing. It has been turned into a museum telling the story of its top-secret past, and hosting the separate National Museum of Computing.

Fenny Stratford Lock marks the end of the Milton Keynes area, and the start of the climb into the Chiltern hills. It’s an unusual lock, with just a small rise of barely a foot: this was the result of problems during canal construction, when difficulty getting the canal north of Fenny to hold water properly led to the section from here to Cosgrove being lowered by a foot, and this lock being added, as a ‘temporary’ measure which became permanent. The lock also features a swing bridge across the chamber, and a pub on the lockside.

In the Buckinghamshire countryside near Cheddington

The proper climbing begins in the next few miles, with a single lock at Stoke Hammond followed by a set of three at Soulbury, and then (after passing through the handy market town of Leighton Buzzard and its canalside partner Linslad), to a long sequence with rarely even a couple of miles’ break as the canal climbs through Grove and Slapton to Marsworth. Here the quiet Aylesbury Arm branches off west, leading down through 16 narrow locks to the Buckinghamshire county town, before the final flight of seven locks, winding around the hillside with views over the complex of reservoirs built to supply the canal, brings us to the Tring summit. All of these locks, incidentally, were also duplicated in the past, with narrow locks alongside the broad ones as a way of saving water when single narrowboats used them – and some traces remain in the form of ‘double bridges’ at the tail of several locks – with a second arch where the second lock once was.

Leighton Buzzard Narrow Gauge Railway

Leighton Buzzard Narrow Gauge Railway

A survivor of the industrial light railways serving the clay, gravel and particularly sand pits around the Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire area, this line, reached by a one-mile walk from the canal in Leighton Buzzard, was rescued from closure by enthusiasts. It operates passenger trains on most Sundays from April to October plus certain other days at holiday times, and maintains a large collection of historic steam, diesel, petrol and battery electric industrial locomotives and associated rolling stock.

The Tring summit begins with a junction where the former Wendover Arm turns off, and thanks to the efforts of the Wendover Canal Trust it could in the not-too-distant future once again allow boats to visit Wendover; in the meantime, the first mile and a half is navigable to Little Tring, and makes an attractive detour with plenty of room to turn round at the end.

The remainder of the three-mile summit level passes through the deep, wooded and gloomy Tring Cutting, leading to Cowroast Lock and the start of the long descent to the Thames. And if the climb up to the summit gave little time for a rest between locks, the downhill journey from here onwards is even more relentless. In the 26 miles to Cowley Lock there are 45 locks, with rarely as much as a mile between them, as the canal passes through Berkamsted, Bourne End, Hemel Hempstead and Kings Langley, with the West Coast Main Line railway and the old A41 main road for company. It also keeps company with a series of small rivers: the River Bulbourne, the River Gade and the River Colne all join and leave the canal at various points – and at times (especially after heavy rain) they add a noticeable flow to the canal.

Berkhamsted’s well-known canalside Rising Sun pub

After Hunton Bridge the railway diverges and the canal passes through a curious length, with a series of sharp bends and two unusually ornamental arch bridges: the explanation is that this section ran through the grounds of the homes of the earls of Essex and Clarendon, who insisted on it being given a more river-like and attractive appearance. An attractive wooded length leads through Cassiobury Park, before a high-level viaduct carrying the London Underground Metropolitan Line reminds us that we’re getting closer to the capital.

The canal takes a south westerly route as it follows the Colne Valley, surrounded by lakes created from former gravel pits as it passes Rickmansworth. This is a handy canalside town with a canal history: it was where boatbuilders Walkers built wooden working narrowboats for many years, including many of the unpowered butties for the Grand Union Canal Carrying Company’s fleet, and the words “Registered at Rickmansworth No xxxx” appear on many historic boats, recalling the days when working boats had to be registered with the local authority if people were living aboard.

Despite having had its first meeting with the Underground, the canal keeps its distance from the metropolis as it skirts the west side, just outside the built-up area, past Harefield and Denham. The locks have finally begun to thin-out a little, with some slightly longer gaps between them. Look out for a few interesting navigation features: the side-lock at Rickmansworth leading to moorings on the River Chess (there was once a third lock leading from there into a gravel pit); Denham Deep Lock, the deepest on the Grand Union with a rise of over 11ft; the former millstream entering the canal from the left-hand side below Coppermill Lock which can catch boaters unawares when it’s flowing fast after heavy rain. And let’s not forget a new feature that’s appeared in the last couple of years: the spectacular new viaduct carrying the HS2 high speed railway line across the Colne Valley and over the canal near Denham.

Leaving Cowley Lock, the last lock for six miles as the crew finally get a rest

Uxbridge marks the canal’s final arrival in the outer reaches of London’s urban area, and surroundings are industrial as the canal continues through Cowley Lock and past West Drayton and Hayes. Two more arms branch off: turning off right at Cowley Peachey Junction is the five-mile Slough Arm, a latecomer to the canal system (Slough is one of the few towns where the railways arrived before the canals); while Bulls Bridge is the junction for the Paddington Arm on the left, beginning its 13-mile level route to Little Venice, Paddington Basin, and onward connections via the Regent’s Canal to East London, the tidal Thames and the River Lee.

Meanwhile, the long sequence of locks has finally come to an end, and a six-mile level pound allows our crew a rest before the view of Norwood Top Lock ahead signals the start of the final descent. In the brief gap after the first two locks, the canal passes “Three Bridges”, a curious combination of structures where a small aqueduct takes the canal over a freight railway line, while both railway and canal are spanned by a road bridge. This is soon followed be the remaining six locks of the Hanwell flight, some fitted with triple sideponds to save the maximum amount of water in the days when supplies to the long level were depleted by the busy local lighterage traffic between the Thames and factories in West London.

Below the bottom lock we meet the last of the series of rivers that share part of their course with the southern Grand Union, as the River Brent enters from the left under a towpath bridge. Watch out once again for the effects of currents, and also for a certain amount of silt brought down by the river. The last couple of miles are a not unattractive length accompanied by parks and playing fields, and spanned by bridges carrying the M4 motorway and the London Underground Piccadilly Line, as well as a Horseley Ironworks cast iron towpath bridge of a type often seen on the Birmingham Canal Navigations system, but a real rarity this far south. A sign proclaiming that this section of canal won the 1959 Kerr Cup for piledriving recalls a time when such things were taken seriously! Two locks accompanied by weirs carrying the River Brent continue the descent.

Brentford used to be a dock town, and the canal was once surrounded by warehouses extending out over the water. These have now gone, but at least one of the new office and residential developments which have taken their place makes use of the canal – albeit in a rather different way. Note the water cascading down the canal bank from an outfall by the GlaxoSmithKline headquarters: the building uses canal water cooling in place of a more conventional air conditioning system.

For those not planning to continue onto the Thames, there are visitor moorings and plenty of space to turn around in the wide basin section of canal before Brentford Gauging Locks. Those continuing around the next stage of the Thames Ring will need to take account of the length of the river from Brentford to Teddington being tidal: this involves booking in advance for the tidal Thames Locks which are keeper-operated and only available at certain times of day and states of tide. See our ‘Brentford to Teddington’ section at the end for information about the tidal trip, but be reassured that although you need to be aware of the tides, in general it’s a much less challenging stretch to navigate when compared to the lower lengths of the tideway through central London with their faster currents and often busy waterbus, trip-boat and freight traffic.

So, you can take it easy, and enjoy being on a wider and completely different kind of waterway compared to the confines of the Grand Union Canal. Passing Kew Gardens on the left and Isleworth (keep left of the island) on the right, the river runs south along Richmond’s busy waterside (you’ll normally go straight past Richmond Half-tide Lock as the moveable weir will have been raised, leaving the main river clear for you to pass), before bending to the west to pass Eel Pie Island, once home to a legendary 1960s jazz, blues and rock venue which hosted everyone from George Melly to Pink Floyd – but which burned down in 1971.

Look out for an obelisk on the left: this marks the change in jurisdiction from the Port of London Authority to the Environment Agency which is the navigation authority for the non-tidal river. But watch out also for the approaches to Teddington Lock.

Arrival at Teddington Lock, the end of the tidal section of the Thames

There are actually three locks side-by-side, but you needn’t concern yourself with the smallest one – at about 50ft by 6ft, the Skiff Lock is said to be the smallest working lock in the country, although it’s seldom if ever used these days. The other two are large, mechanised, keeper-operated locks, with illuminated arrows to indicate which one you should use – the Barge Lock, some 650 feet long (I’ve seen an entire convoy of a couple of dozen narrowboats share it), or the more modestly sized Launch Lock at a mere 180ft or so.

Those who haven’t already bought an Environment Agency Thames licence (or a ‘Gold Licence’ covering both the EA and Canal & River Trusts waterways) will need to moor up just past the lock and report to the lock keeper’s office, where short-term licences (actually ‘registrations’, technically) can be bought. While you’re there, look out for the plaque on the lockside commemorating the filming of the Monty Python fish-slapping dance on this site, before returning to your boat and heading up-river.

Passing Kingston upon Thames, the river makes a long, sweeping right-hand bend around Hampton Court Park to pass the palace (see inset) on the approach to the first lock on the non-tidal river, Molesey Lock.

Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace

Directly alongside the Thames just downstream of Molesey Lock is this famous building, created for Cardinal Wolsey but taken over as a royal palace by Henry VIII. Today it’s open to the public who can see the state apartments, Tudor kitchen, cloisters, formal gardens, and of course the famous maze.

At this point, up to a few years ago I would have explained about all Thames locks being staffed, and that boaters need to follow the lock keeper’s requests regarding which side of the lock to go on, and then to stop their engine and hold their boat on ropes fore and aft (as required under the Thames regulations) and wait for it all to be done for them. But in recent years reductions in staffing have meant a greatly increased likelihood of finding a lock unstaffed and with signs out telling boaters that they will need to operate the lock. On the plus side, at least all the powered locks (that’s all the locks downstream of Oxford) have now been fitted with powered boater operation from a control panel on the lockside, rather than the hundreds of turns on a hand wheel which used to be the only way to work them outside of keepers’ hours until the 1990s or so (and is still very occasionally needed if the power is off for any reason).

On the subject of signs that you might see at locks, there are also ‘red boards’ (danger, strong stream conditions, you are advised not to navigate) or ‘yellow boards’ (caution, stream increasing – or decreasing – navigate with care) to look out for after heavy rain.

After passing Sunbury and Walton, there’s a choice: boats can go straight ahead to follow the Desborough Cut, a mile-long artificial channel, or bear right to follow the longer original (and rather winding) river channel past Shepperton. The two meet again at a complicated junction of weir streams and backwaters: the entrance to Shepperton Lock is clearly visible ahead (and a little to the right); less obvious is the approach to the River Wey Navigation which joins the Thames here after its journey down from Godalming and Guildford. To get to it, you’ll need to take the channel to the left of Shepperton Lock, and then take the second-from-left of the four channels into which it splits.

The locks come fairly regularly at an average of one every three miles as the river passes the riverside towns of Chertsey and Staines, then a less populous stretch passes Runnymede, with Magna Carta Island, and the adjacent memorial park with monuments to the Magna Carta, John F Kennedy, and the Commonwealth Air Forces. Passing Old Windsor on the south bank then Datchet on the north side, the Jubilee River (an unnavigable flood relief bypass channel for the Thames between here and Maidenhead) enters on our right, and a long lock cut curving to the left brings us to Romney Lock, and the start of Windsor.

Leaving the lock, boats soon arrive in the heart of Windsor, with the castle in its commanding position to the left, Eton College facing it across the river, and (at least in summer) trip boats, smaller craft and visitors everywhere. It’s a good place to stop (there are visitor moorings on both banks upstream of the town centre) before cruising the final part of the Thames Ring next month.

Brentford to Teddington

The length of the River Thames from Brentford to Teddington is tidal, and while taking a narrowboat or other inland craft on it is a lot less adventurous than cruising the busy stretch of the tideway through central London, it still does require some awareness and planning.

Timings: Thames Locks, the paired final locks at Brentford which lead from the Grand Union into the Thames, are keeper-operated and need to be booked at least two working days in advance by phone or email (see canalrivertrust.org.uk for details). They are only open within certain hours, and in addition they can only be operated from two hours before high water to two hours after high water. (High water is one hour later than the time given for London Bridge – and don’t forget that tide tables often give times in GMT, even during the summer time, so you will have to add an extra hour for that). In practice the lock keeper’s advice is generally to leave Brentford soon after the locks open, so that you will be travelling with the incoming tide from there to Teddington. On the return trip, leaving Teddington at or shortly before high water there will ensure that you are going with the falling tide for most of the way, and that you will still have enough time to get through Thames Locks at Brentford before they close.

Richmond half-tide lock: part way along the tidal length at Richmond there is a moveable weir accompanied by a lock. From two hours before high water to two hours after, the weir is raised and boats can pass straight through. At other times, the weir is in place to retain enough water for navigable depth between there and Teddington, and boats need to use the lock. If you use the timings suggested above, you will not normally have to do this.

Brentford High Street Bridge: on certain particularly high tides, the length of canal above Thames Locks at Brentford becomes tidal as far as Brentford Gauging Locks for an hour or two around high water. It can rise by several feet, leaving insufficient headroom for most boats to pass under Brentford High Street Bridge. Again, this will not normally affect you if you follow the suggested timings above, but be aware of it if you plan to moor for any time on the length between the two locks.

Radio: The is a requirement for marine band VHF radio for boats over 45ft long using the Thames tideway; however, an exemption applies to narrowboats travelling between Brentford and Teddington, so long as they phone the Port of London Authority immediately before and after the tidal passage.

Currents: be aware that you (and other boats on the river) will be affected by tidal currents. If following the above guidance this will tend to help you on your way, but do remember to allow for it by making any manoeuvres (such as lining up for bridges or for passing other craft) in good time. And be sure to swing wide rather than cutting the corner as you round the turn between the canal and the river at Brentford, as there are shallows on the inside of the turn, and if the tide is rising it will tend to push you towards them.

General: you are advised to wear lifejackets, check that your insurance covers tidal waters, put your anchor out ready to deploy if necessary, and be sure to carry out your usual checks: weed hatch, sterngland, engine oil, coolants etc.

As featured in the May 2025 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the May 2025 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here