The North Wilts Canal at Latton might not be on the navigable network for some years to come, but that hasn’t deterred a local group from preserving what survives of this long-lost rural length of waterway – and creating a circular walk for us to enjoy today. Martin Ludgate has been finding out more…

You have to feel sorry for the North Wilts Canal. Not only has it been shut for over 100 years (and been subjected to the usual ignominies such as demolished bridges, missing aqueducts and having part of Swindon built on it), but both of the two canals that it once connected together have also been abandoned for a similar length of time.

So it’s a derelict canal isolated from the outside world by derelict canals on either side of it. Rather like being a landlocked country that’s completely surrounded by other landlocked countries (Uzbekistan and Liechtenstein, since you asked…), its status seems to give it an added level of remoteness when it comes to any possible prospects of its revival.

The stop lock at Latton: in ruins but recognisable and being preserved

And yet, with the world of canal restoration being the optimistic movement that it is, this hasn’t prevented anyone from putting the North Wilts forward as a candidate for restoration. After all, the two canals that it linked are both the subject of well-established restoration projects which have chalked up some significant success stories in recent years.

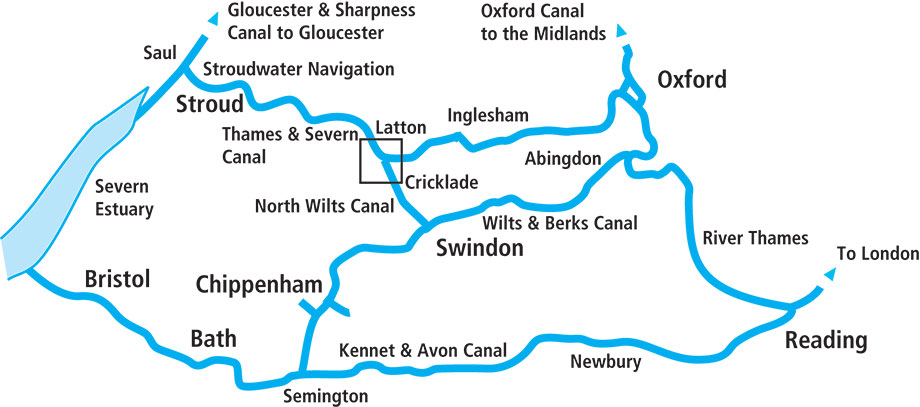

To the north, the Cotswold Canals Trust is pressing ahead with plans to reopen the Stroudwater Navigation and the Thames & Severn Canal, which between them connected the Gloucester & Sharpness Canal at Saul Junction to the upper River Thames at Inglesham. Work has been carried out at various sites along the route, and while most recent effort has been concentrated on the Lottery-funded schemes at the west end whose completion will see boats cruising from Saul to Stroud and beyond in a couple of years, the Trust still has its sights on reopening the entire through route. Meanwhile to the south, the Wilts & Berks Canal Trust is equally determined to eventually reopen another east-west through route, from Abingdon on the Thames to Semington on the Kennet & Avon Canal.

Reopening these two routes would open up two new through routes across southern England. But restoring the North Wilts as well would turn them into a “Wessex Network” of waterways, combining with the Thames and the K&A to create all manner of rings and through routes.

The Wilts & Berks Canal Trust includes the North Wilts in its remit (it was built as a branch of the W&B) and has carried out various projects on it over the years, restoring the Moredon and River Key aqueducts and Moulden Lock, as well as getting one road bridge on the north side of Swindon built with navigable headroom. However its main thrust in recent years has centred on the length of the Wilts & Berks from west of Swindon to Royal Wootton Bassett, with the opening up of another section at the Melksham end also on the horizon. So although there’s a long-term commitment to reopening the North Wilts and a purpose in doing so, its remoteness from the action means it’s not currently top of the agenda for either of these major restoration trusts.

The largely restored chamber of Cerney Wick Lock with its distinctive roundhouse lock cottage

NEW ENTRY

Enter a new group, called Latton Basin Restoration, Latton being the junction at the north end of the North Wilts Canal where it meets the Thames & Severn. And one of the first things they explained to me when I caught up with them on their stand at the Inland Waterways Association’s Festival of Water at Burton-upon-Trent was that “we aren’t a canal restoration group”. So what exactly is their role?

By way of explanation, let’s start with a little background information regarding the current state of the North Wilts Canal and WBCT’s long-term restoration plans for it. At the south end, its first couple of miles run through Swindon and have been built on in places, although there’s a surviving section that’s used as a cycleway – including a handy surviving bridge under the Great Western main line railway. Further north the canal (or in places its infilled route) survives in better condition with fewer serious obstructions, and this is where the above-mentioned completed restoration projects are situated.

But approaching Cricklade, restoration gets trickier again. A tunnel which burrowed under part of the town is now blocked at both ends, and on either side of it houses have been built on the site of the approach cuttings. Proposing to reopen the canal on its original route would not be popular – so WBCT has looked at various options for diversions. These might go either side of the town, and depending on which option is eventually chosen it might rejoin the original route or it might meet the Thames & Severn at a completely new junction, probably further east than the original one.

That decision might not be taken for quite some time – so whether the final length of canal to the original Latton Junction will one day be restored or will be bypassed by a new route isn’t known. And that’s unfortunate, because it’s an interesting length, with some fairly well-preserved features (at least by the standards of canals that have been left to decay for a century) which it would be a shame to continue to neglect. But at the same time it makes no sense for WBCT to put effort into restoring this section which might never be needed, when there are many other potential restoration projects elsewhere on the Wilts & Berks where there are no such doubts. So (as explained in our ‘Preservation Work’ panel opposite) the new group aims to save what’s left at Latton, and you can see what they’ve already done by following the circular walk they’ve created.

Remains of abutment and surviving arch of the River Colne aqueduct

WALK THE LOOP

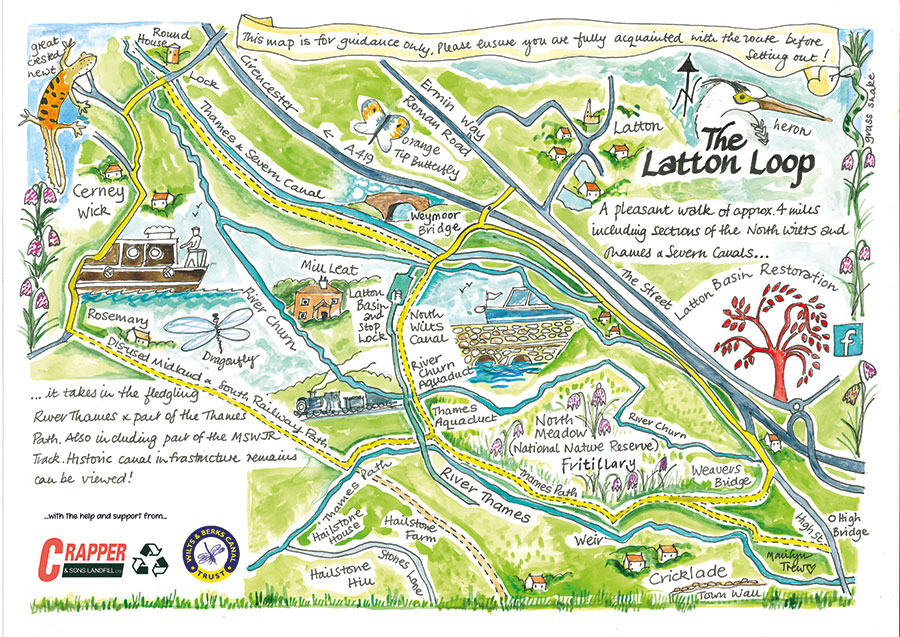

We walked the Latton Loop to see for ourselves the historic features that the new group have been working to save – and to spot various other surviving pieces of canal and railway heritage along this pleasant circuit.

A good place to start is at Cerney Wick. By the Crown Inn, a minor road (signposted to Cricklade and Down Ampney) turns east off the village main street, and after a few hundred yards it crosses the Thames & Severn Canal. You’ll be turning right here onto the canal towpath, but first take a look on the other side of the road, to your left. Immediately adjacent to the road crossing is Cerney Wick Lock, built (as were all bar the westernmost few of the Thames & Severn’s locks) to dimensions of around 90ft by 12ft to accommodate the traditional Upper Thames barges which traded onto the canal.

The lock chamber was largely restored many years ago by the Cotswold Canals Trust, but won’t see any boats until the demolished road bridge which once crossed its tail has been reinstated. It does have one really noteworthy feature: a ‘roundhouse’ cottage. Five of these circular buildings were built at intervals along the canal to house lock keepers or lengthsmen. There were two patterns: this one, which survives in private ownership, has a pointed roof; others have an even more curious inverted roof, pointing downwards in the middle to collect rainwater.

Walk south along the towpath (it’s signposted as a public footpath to Cricklade) alongside the weed-filled channel, and you’ll pass a couple of canal mileposts. Used to calculate mileage-related freight tolls, these were installed at half-mile intervals, and give the distances to the nearest quarter-mile east to Inglesham and west to Wallbridge (the mileposts use the older spelling of ‘Walbridge’) in Stroud, where the Thames & Severn Canal ended and the Stroudwater Navigation began.

You’ll see ahead of you the high hump-backed Weymoor Bridge, which carries an access lane across the canal for local residents and farm traffic. It may look (at least from a distance) like an original structure, but was in fact a complete rebuild by Cotswold Canals Trust in recent years from the remains of the abutments upwards, the original having been demolished and the lane diverted across the canal bed alongside it.

The decision to work on this site some distance from the main focus of CCT’s attention was driven by a legacy given to the Trust for this particular project. The new bridge had to not only withstand modern farm traffic but look like the 18th-century original which had been built for nothing heavier than a horse and cart. Having done some of the bricklaying on a Waterway Recovery Group volunteer canal camp, the author recalls that it was an interesting job.

A towpath footbridge replaces the missing aqueduct over the infant River Thames

FINDING EVIDENCE

Beyond the bridge the Thames & Severn Canal continues, before it disappears under the modern A419 dual carriageway built in the 1990s (the subject of a huge – and successful – campaign by canal supporters at the time to get a buried navigable culvert constructed which will eventually take the restored canal under the road). But we’re going to take a few steps back, because this is also the site of Latton Junction where the North Wilts Canal branched off.

Just north of Weymoor Bridge you might have noticed a slight widening of the canal, and the towpath diverging slightly to the west. This was the turning basin at the old junction, and the towpath used to cross the entrance to the North Wilts on another bridge. It’s long gone, but you can still see two lines of stonework buried in the path, showing where the sides of the canal channel under the bridge were.

Now look over the hedge, away from the Thames & Severn Canal, and (depending on how tall you are and how much the hedge has grown) you should be able to make out where the canal crossed another small watercourse (the River Churn mill leat) on a small aqueduct (also demolished but with traces of stonework remaining), before entering a large (and well-preserved) basin. This was where boats once moored while cargoes were transhipped between the Upper Thames barges and the smaller 70ft by 7ft narrowboats used on the North Wilts Canal. Although it’s not publicly accessible (so please don’t go exploring) you should be able to make out where the Latton Basin Restoration team have been working to conserve the masonry of the basin.

Now take the towpath south, but instead of turning left into the lane to cross Weymoor Bridge, turn right towards the privately owned original canal junction cottage. Before you get to the house, take the public footpath which bears left off the drive. This leads past the house and across a footbridge over a ditch to where you’ll see the next of the historic structures that the volunteers are working to save: the four-arch flood relief aqueduct built to carry flood water under the canal. Part of one of the four arches had collapsed, but the volunteers are rebuilding it.

Continuing past the aqueduct, the path climbs to join the original towpath, and here you’ll see that leading on from the top of the aqueduct is another structure. This is the first of the North Wilts Canal’s 11 locks, and was in fact simply a stop-lock to regulate the flow of water between the canals, with no significant rise and fall. Although one could hardly say that it’s in good condition, it’s recognisable as a lock, it’s clearly narrower than the ones on the Thames & Severn, and the volunteers are hard at work on saving the brick and stone structure.

Continuing south along the towpath, the channel is clearly well-defined, the canal running on an embankment and around a left hand bend as it crosses the Thames flood plain. The next historic structure is the River Churn Aqueduct, and there’s rather less to see of it as the main structure has been demolished. However a surviving abutment wall and one arch have been uncovered and the decayed brickwork is being repaired.

Weymoor Bridge has been rebuilt by volunteers (including the author of this article)

INFANT THAMES

In the absence of the aqueduct a footbridge takes walkers across the Churn, before the next length of canal leads to the site of the Thames aqueduct. There’s even less to see of this, although some historic fabric may survive in the footbridge abutments, and beyond there the canal soon disappears on the approach to Cricklade. But we’ll turn off right here, to take the Thames Path as it follows a stream so small that it’s hard to think of it as the same river that flows through London. The infant Thames meanders through watermeadows for half a mile to reach another bridge, which carried another long-lost transport route.

The Midland & South Western Junction Railway once ran from near Cheltenham via Cirencester and Swindon to Andover. It provided a useful freight route from the Midlands to the port of Southampton, but it was never a busy or profitable passenger line. In fact it didn’t even last until the controversial Beeching closures of the 1960s, having already lost its passenger trains in 1961 – although the length from Swindon to Cirencester carried freight for another three years.

But almost 60 years since it saw its last goods train, part of this section is now a footpath and cycleway, and we’ll turn right and follow it northwards from this bridge (Incidentally a few miles south another section of the same line is gradually being reopened to heritage steam services as the Swindon & Cricklade Railway).

The old railway runs through an area of nature reserves: the line and its embankments form a wildlife corridor and home to bats (roosting in bridge arches), badgers, woodpeckers and glow-worms; it also connects to other sites including the North Meadow National Nature Reserve, Elmlea Meadow and many of the lakes formed from old gravel pits which make up the Cotswold Water Park.

A really quite remarkable nine-arch bridge carries a small country lane over the old railway, but before you get to it you’ll need to turn left and right to follow another track which runs parallel to the railway and brings you out onto the lane. Turn right, cross the railway bridge and it’s a half mile walk along country lanes and through the village to the Crown Inn where you started – and an excellent place to refresh yourself after your walk.

Latton Basin Restoration Group

The Latton Basin Restoration group was founded by local enthusiasts with the aim of conserving and preserving what’s left of the canal and its historic structures, and stopping them decaying further. It’s very much a local community group, and it’s already made practical progress on saving the structures. Its view is that there’s a chance that one day they may be needed as part of the eventual navigable canal route – in which case the group’s work now will help to preserve them for future restoration and reopening. But if that never happens, then the structures have been preserved as a part of the canal’s heritage – and there’s always the possibility that part of the old route could be reinstated as (for example) an off-line mooring basin. So whatever happens, they see these relics as worth conserving – and as a largely local group they aren’t taking valuable effort away from more pressing projects on the Wilts & Berks. So who will actually appreciate these lost fragments of 200-year-old waterway heritage? Well, potentially, quite a few people. The towpath survives as a footpath and forms part of the Thames & Severn Way, a long-distance route which also incorporates an adjacent length of the Thames & Severn Canal. Not only that, but it links up to the Thames Path, a source-to-sea trail along the Royal River (which in these western parts is actually a smallish stream), which in turn connects to a nearby disused railway line which has been opened up as a footpath (and part of the National Cycle Network). Add in a half mile of country lanes through Cerney Wick village, and you’ve created the ‘Latton Loop’ – a four-mile circular walk.

The Latton Basin Restoration group was founded by local enthusiasts with the aim of conserving and preserving what’s left of the canal and its historic structures, and stopping them decaying further. It’s very much a local community group, and it’s already made practical progress on saving the structures. Its view is that there’s a chance that one day they may be needed as part of the eventual navigable canal route – in which case the group’s work now will help to preserve them for future restoration and reopening. But if that never happens, then the structures have been preserved as a part of the canal’s heritage – and there’s always the possibility that part of the old route could be reinstated as (for example) an off-line mooring basin. So whatever happens, they see these relics as worth conserving – and as a largely local group they aren’t taking valuable effort away from more pressing projects on the Wilts & Berks. So who will actually appreciate these lost fragments of 200-year-old waterway heritage? Well, potentially, quite a few people. The towpath survives as a footpath and forms part of the Thames & Severn Way, a long-distance route which also incorporates an adjacent length of the Thames & Severn Canal. Not only that, but it links up to the Thames Path, a source-to-sea trail along the Royal River (which in these western parts is actually a smallish stream), which in turn connects to a nearby disused railway line which has been opened up as a footpath (and part of the National Cycle Network). Add in a half mile of country lanes through Cerney Wick village, and you’ve created the ‘Latton Loop’ – a four-mile circular walk.

As featured in the January 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the January 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here