In the first part of our guide to the great southern circuit of waterways, we follow the windings of the narrow Oxford Canal north from Banbury, before taking the contrasting broad Grand Union Canal south east through Braunston to Stoke Bruerne.

Words and pictures by Martin Ludgate

Three contrasting waterways – one wide canal, one narrow canal, one river – make up a 246-mile circuit which we call the Thames Ring. That isn’t the only name that it’s known by – you’ll sometimes also see it referred to as the Grand Ring. But I’ve also seen that name used (admittedly a while ago) for a large circuit of northern waterways. So rather than risk starting any “my cruising ring’s grander than yours” type arguments, we’ll stick with Thames Ring.

Three contrasting waterways – one wide canal, one narrow canal, one river – make up a 246-mile circuit which we call the Thames Ring. That isn’t the only name that it’s known by – you’ll sometimes also see it referred to as the Grand Ring. But I’ve also seen that name used (admittedly a while ago) for a large circuit of northern waterways. So rather than risk starting any “my cruising ring’s grander than yours” type arguments, we’ll stick with Thames Ring.

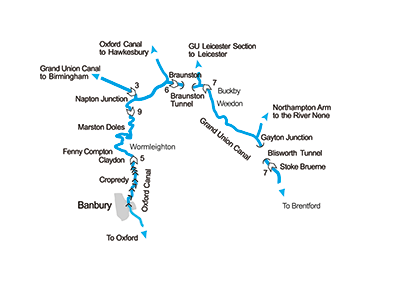

That gives us the identity of one of the three waterways – the River Thames, which we’ll follow from Brentford, on the west side of London, to Oxford. There it meets the second of our three waterways: the Oxford Canal. We’ll take this from Oxford northwards to Napton and Braunston, where we join the third and final waterway. This is the Grand Union Canal, on which we will cruise south eastwards to return to the Thames at Brentford.

It’s a circuit which could be completed in a fortnight if you like long days of boating; three weeks would make for a much less energetic trip; four or more if you really want to take your time and see everything on the way (and maybe make a side-trip to the top of the Thames).

Those three waterways might seem to fit very nicely into a three-part article, with the three parts beginning at Oxford, Braunston and Brentford. But actually, to give you more of a feel for the variety of waterways that we’ll traverse, we’re going to start each instalment part-way along one of the three. And this time we’ll set off from Banbury, the only canalside town that the southern Oxford Canal passes through on its way from Oxford to Braunston.

Banbury has earned a bit of a bad press in the past as regards its treatment of its canal – the old basin was filled in in the 1960s to make space for a bus station, and the town turned its back on its waterway. But more recently this has been replaced by more modern town centre redevelopment schemes including Castle Quay, and while the architecture might not be to the taste of traditionalists, it certainly faces the canal, and attracts plenty of people out onto the towpath or to watch boats passing through the first of the 175 locks on our circuit.

A wooded length near the south end of the Oxford Summit

This is a typical narrow lock built for the traditional 70ft by 7ft narrowboat of the Midlands canals, and as we head northwards it’s closely followed by another structure that’s very much a southern Oxford Canal speciality, rather than a typical narrow canal feature. Simple hand-operated wooden drawbridges, opened by pulling down on chains attached to the balance beams, were an expedient said to have been adopted for many farm crossings and footpaths to save money (compared to brick bridges) when the canal company’s finances were getting stretched as it struggled to complete its route south to Oxford. And that seems to ring true, with these lift bridges getting more common the further south you go.

Actually, what I said about the bridges being operated by chains isn’t true of this one – it’s operated by using a lock windlass to turn the spindle on the hydraulic gear that raises and lowers the bridge. There is currently a programme of work to convert all the lift bridges which boaters are likely to need to open (i.e. not the ones that are normally left open unless the farmer needs to use them) to this system, so in a year or two’s time, dangling on chains will be a thing of the past.

Tooley’s Boatyard

Tooley’s Boatyard

Dating right back to the earliest days of the canal, Tooley’s heritage boatyard is a piece of living history with its old forge, historic drydock and traditional drive-belt system – but it’s also still a working boatyard. It’s open for tours every Saturday from mid-April onwards. See tooleysboatyardtrust.org.uk

The visitor moorings in this area are very handy for the useful shopping centre, and also for visiting the one remaining traditional canalside business: Tooley’s Boatyard, where waterways revival pioneer Tom Rolt had his boat Cressy fitted out before embarking on the 1939 journey that he recounted in his classic Narrow Boat, the book credited with starting the campaign to save the canals.

After a mile of cruising past Banbury’s industrial outskirts, the town is left behind, the M40 motorway (which has been following the canal for a few miles) crosses one more time and heads west, and we’re left in peace as the canal follows the upper Cherwell valley northwards. The River Cherwell is little more than a stream here, although that can change dramatically after heavy rain, occasionally with serious consequences for the canal.

Locks occur occasionally, as the canal continues its gentle climb towards its summit. There’s a particularly attractively situated one at Cropredy, a pretty village famous historically for its Civil War battle and these days for the annual Fairport’s Cropredy Convention folk and rock music festival. Boaters may also be interested in its two pubs.

The climb steepens with three locks in quick succession followed by five-lock Claydon flight which brings us to the 11-mile summit level. Sadly, Claydon village, a little way to the west, has lost both its pub and its remarkable Bygones museum, full of things to make you go “I remember we had one of those…”

The summit begins with some gentle windings as the canal follows the contours, then enters a curious long, straight, narrow cutting. A clue to its origins is that it is known locally and by boaters as “The Tunnel”, a name that the working boat crews were still using many years after the former 1,138 yard Fenny Compton Tunnel was opened out into a cutting in stages between 1838 and 1870 as a result of it being a bottleneck for traffic.

The Canal Museum

The Canal Museum

Housed in a former flour mill building in Stoke Bruerne, the museum tells the story of the canals and the people who worked on them, with working models, displays and exhibits including painted ware and canal crafts, traditional clothing, signs and tools – plus the restored historic former working boat Sculptor moored outside.

It’s once you’ve left ‘The Tunnel’ behind and passed the handy boatyard and pub at Fenny Compton that the Oxford summit starts to take on the character that it’s well-known for. Clinging to the contour, it winds this way and that, doubling back on itself and snaking around three sides of Wormleighton Hill as it negotiates the hilly terrain with the minimum of earthworks. It may be eleven miles by water between the locks at either end of the summit, but it’s barely four miles as the crow flies. Of course, there was much to be said for avoiding unnecessary embankments and cuttings in the early days of canal building, and the famous early canal engineer James Brindley (who carried out the original surveys for the Oxford Canal) was a proponent of contour canal construction, but it seems that his pupil Samuel Simcock who took over as engineer for the completion of the work after Brindley’s untimely death may have taken it a little too far. Some 18th century wag once remarked that Simcock seemed determined to sign his initials in water across the countryside!

Although indirect and no doubt infuriating to working boat crews, today it’s a wonderfully attractive and remote length of completely rural waterway. Well, almost completely rural: for a short distance towards the northern end it currently turns into a building site, because this is where the HS2 railway will cross the canal on its way from London to Birmingham, and the new three-arch viaduct over the canal and an adjacent road has been starting to take shape since last year.

Leaving the railway worksite behind, the canal makes a final few zigzagging turns before arriving at Marston Doles Top Lock. Incidentally, it’s preceded, like many of this canal’s locks, by a small sign a short distance before the lock carrying the letters ‘DIS’. These are lock distance markers, installed by the Oxford Canal Company in response to complaints of fights breaking out between boat crews arriving at the same lock from opposite directions and arguing about who had the right to use the lock first. The idea was that if boaters sounded their horn (or in horse boating days, cracked their whip) when they passed the sign, they would know which boat was closest, and had the right to use the lock first. I can’t help thinking that this was open to abuse (what’s to stop you cracking your whip early?) and was perhaps more a case of the canal company being seen to be doing something, rather than an actual solution!

On the five-mile length from Napton to Braunston that’s shared between the Oxford and Grand Union routes

The two Marston Doles locks are soon followed by the main Napton flight of seven locks, an attractive flight with views ahead of the hilltop windmill above the appropriately named Napton-on-the-Hill village. Theres a welcome canalside pub near the bottom lock, and the village is a half-mile walk away. Continuing its meandering route, the canal skirts Napton Hill clockwise, to reach Napton Junction (or Wigram’s Turn, the working boat people’s name for it, which has now given its name to one of several marinas around the junction).

From here onwards the canal changes its character: we’re still technically on the Oxford Canal, but we’re on a five-mile length which also forms part of the Grand Union Canal’s London to Birmingham route, and was enlarged to that company’s broad-beam dimensions as part of its great 1930s rebuilding scheme. So, while the canal still meanders like the Oxford Canal, its bridges and channel are to more generous dimensions. On arriving here in 1939 when the southern Oxford was a quiet backwater, Tom Rolt described it as like leaving a country lane for a main road; while these days, the Oxford Canal is as busy with leisure traffic as the Grand Union, it still has a little of that feel.

Nearing Braunston, the canal follows a more direct route through a straight cutting followed by a lengthy embankment: these date from the Oxford Canal improvement scheme of the 1820s, when the northern section of the canal from here to Hawkesbury Junction (which had originally been just as circuitous as the summit level) was drastically straightened and shortened by a series of new short-cuts which bypassed many miles of its original line, and shortened it by 14 miles.

The embankment leads to Braunston Turn, a junction spanned by a fine pair of Horseley Ironworks cast iron towpath bridges. A left turn here leads to the northern Oxford Canal for Rugby and Hawkesbury Junction; we’ll bear right for the Grand Union route south eastwards towards London.

Although a modest-sized village not widely known beyond the immediate area, Braunston has a much greater importance to the waterways network as the meeting point of two trunk routes, and was major canal centre in working boat days, with boatbuilding yards and carrying companies based there, and many members of boating families christened, married and buried at the village church whose spires is a dominant feature of the hill-top village and visible from some distance. Today it retains its waterways importance with its marina, many boating businesses, and annual historic narrowboat rally attracting many historic craft every June. It’s also a handy stopping point with shops and pubs. And as we head east along the Grand Union Canal, it’s where we can really appreciate that we’re on a different canal now.

The six locks climbing up from the junction were built as part of what was then the Grand Junction Canal from Braunston to Brentford, a later route than the Oxford and one designed by a different engineer – William Jessop. As with a number of canals from that era (and that engineer), it was built broad-beam in the hope of establishing a larger-gauge system reaching across the country by widening existing narrow-beam routes. However, it was not to be, and the majority of cargo-carrying craft using the canal were narrowboats. But today, widebeams are increasingly common, while pairs of narrowboats can share the wide locks side-by-side.

Not far beyond the top lock is Braunston Tunnel, one of two lengthy tunnels on the Grand Union Main Line as it negotiates the higher ground of Northamptonshire. Having been built broad beam, the tunnel is wide enough for narrowboats to pass each other underground: given its 2,042 yard length, it would create a serious bottleneck at busy times if it were restricted to single-direction traffic. This does actually happen on certain early mornings before 9am, which is when widebeam boats are allowed to pass through (having booked in advance with the Canal & River Trust) and other boats may have to wait. Watch out for the slight kink in the middle of the tunnel where the gangs of tunnellers working towards each other didn’t meet up quite as accurately as they might have hoped! There’s no towpath through the tunnel, but the old horse-path that boat horses used to bypass the tunnel is still easy to follow for walkers.

Emerging into a long cutting followed by a quiet stretch of countryside, the canal continues level to Norton Junction, another important meeting-point of waterways, where the long Leicester Line of the Grand Union begins its northward journey to Leicester and the River Trent. Not far beyond the junction, the summit ends as the first of the Buckby flight of locks (accompanied by a lockside pub) begins the descent.

These locks are deeper than those at Braunston, and were each equipped with water-saving side-ponds – although they have been out of use for many years. The quiet countryside is replaced by a rather noisy combination of adjacent transport route, with the canal running parallel to the M1 motorway, the West Coast Main Line railway, and the A5 (originally the Watling Street Roman road). The reason is that these routes all took the same handy route through the hills, the ‘Watford Gap’ (which gave its name to the motorway service station a mile or two to the north).

Stoke Park Pavilions

Stoke Park Pavilions

Reached by a footpath from the towpath by Lock 15 in Stoke Bruerne, these two matching structures and the attached colonnade are all that was left after the rest of the 17th century Palladian Stoke Park House burned down in 1886. They can be visited, along with the gardens, for a small entry fee every afternoon in August and at other times by appointment.

A marina with boatyard accompanies the bottom lock, before the motorway diverges and the canal meanders through quieter country, albeit with the railway still close by. Lock crews will get a rest, as there are none for 13 miles. Weedon is a handy village with shops, pubs, and the remains of a very short but rather unusual waterway, which we describe in our Cruise Guide Extra on the pages following this article. Nether Heyford and Bugbrooke villages are also within walking distance of the canal.

At Gayton Junction, the canal’s Northampton Arm turns off to the left: although its principal use is as the only navigable inland route to the River Nene (and from there to the Fenlands and the Great Ouse system), it’s an attractive if energetic cruise in its own right, with 17 narrow-beam locks in the five miles to the Northamptonshire county town. Do note that if you’re continuing onto the River Nene, this is not a CRT waterway and so you’ll need the appropriate Environment Agency registration and key to operate the lock gates (both available from Northampton Marina).

On the 13 mile level pound from Buckby to Stoke Bruerne

Back on the main line, the canal passes Blisworth village before diving into the second and even longer tunnel. At 3,056 yards, Blisworth Tunnel is (after Standedge) the second longest in regular use on the network. Like Braunston, it normally takes two-way traffic in narrow beam craft, with widebeams restricted to pre-booked passages on certain mornings. There’s also a tunnel top horse-path for walkers, although it’s not quite so easy to follow as at Braunston.

You’ll notice that the tunnel’s profile changes as you pass through: it begins as a traditional brick-lined bore, then for about one-third of its length it switches to a modern concrete construction, before changing back to brick for the final section.

This is a reminder of the major rebuilding that took place following the ‘Tunnels Crisis’ of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when many canal tunnels were showing their age and becoming unsafe, resulting in a series of indefinite closures around the network – and eventually in extra Government money to rebuild them.

Less than half a mile beyond the tunnel, the canal arrives at Stoke Bruerne, another famous canal village, with its waterways museum (see inset), pubs, flight of seven locks and attractive setting. It’s a good place to stop for a short while before we continue our journey around the Southern Ring next month.

As featured in the April 2025 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the April 2025 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here