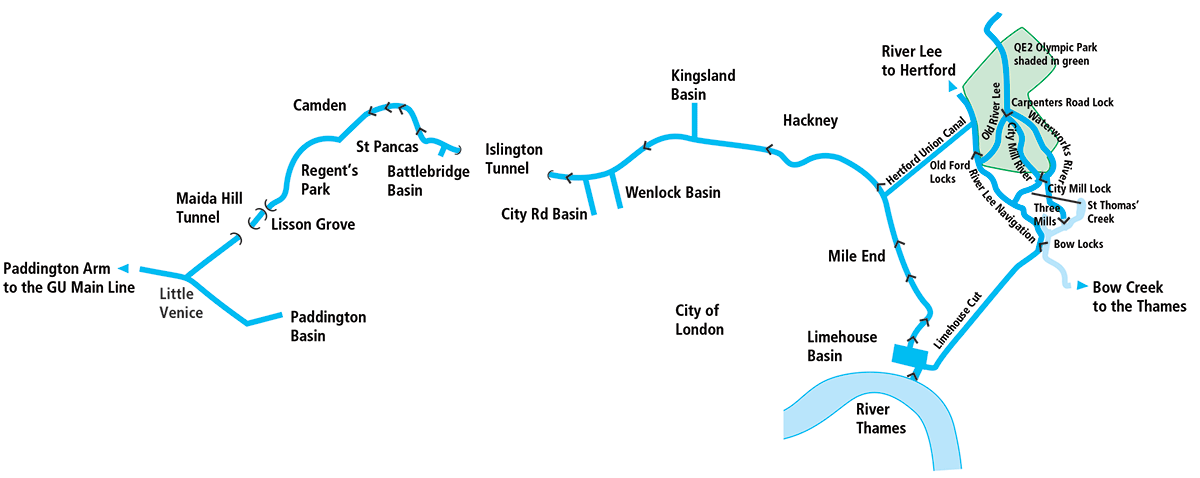

It’s one of our shorter waterways, but London’s canal packs in a lot of interest in its journey from Little Venice through the capital to Limehouse and the docklands

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

At just under nine miles long, London’s Regent’s Canal is one of the shorter canals on the network – and probably the shortest that we’ve ever dedicated an entire cruise guide to. But despite its modest length, lack of spectacular engineering or splendid rural scenery, and entirely urban route, it packs a huge amount of interest into that length.

Built to link the Paddington Arm of the (then) Grand Junction Canal near its Paddington Basin terminus to the docks in East London, the canal skirts around the northern limits of Westminster, the West End and the City as it descends through 12 locks to the Thames at Limehouse Basin. In doing so, it runs within easy reach of may of the capital’s attractions, quite apart from all the interesting features of the canal itself, and its immediate surroundings.

Why Little Venice?

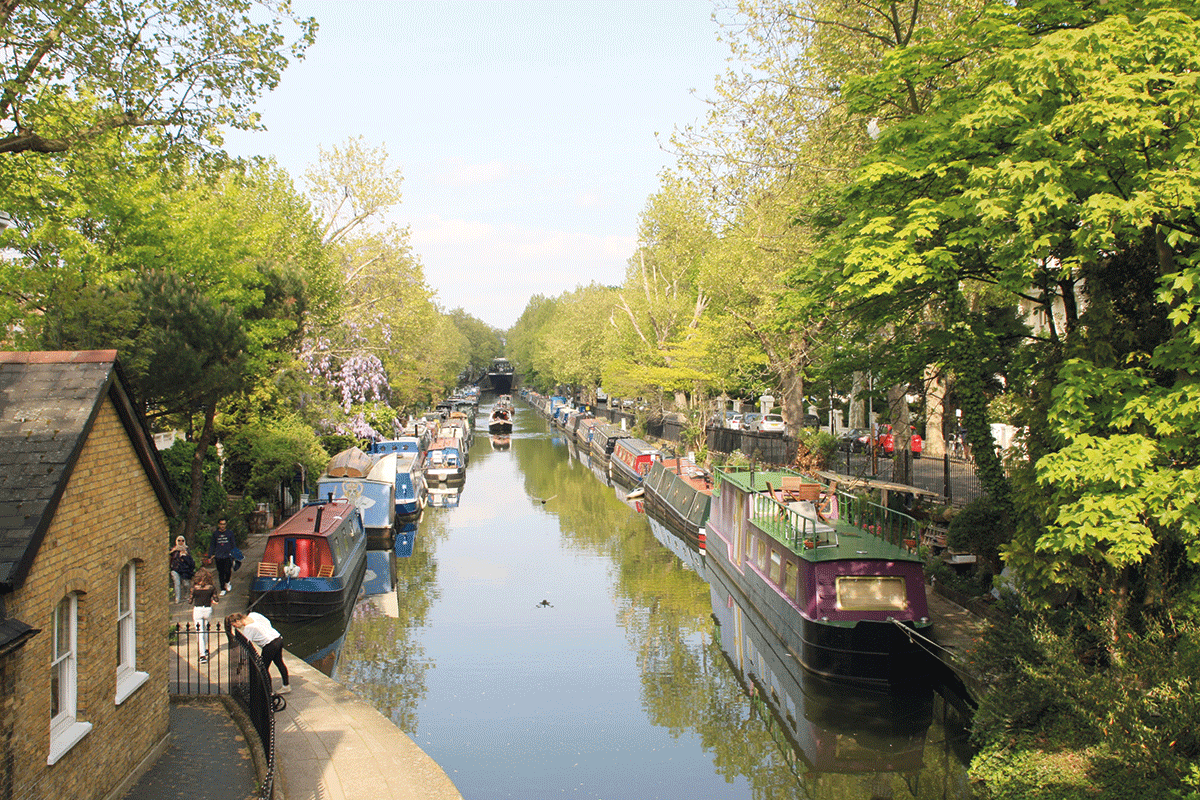

And those interesting features begin right at the start, where it leaves the Paddington Arm. Boats arriving from the main line of the Grand Union pass under a bridge and through a set of former stop gates accompanied by an old toll house (where until the mergers of the late 1920s and early 1930s brought the Regent’s and the Paddington Arm under the same canal company, tolls would need to be paid). From there they emerge into the spacious expanse of water that we now know either as Browning’s Pool or more usually as Little Venice.

The Browning’s Pool name is believed to come from the poet Robert Browning who returned from Italy to live nearby in Warwick Crescent in the 1870s after his wife died. He’s also sometimes credited with being the instigator of the Little Venice name; an alternative claim is that the comparison was made in jest by Lord Byron, soon after the canal had opened (Byron died in 1824). Whatever the case, the name wasn’t in general use until the mid 20th century.

Little Venice is an attractive scene with elegant Victorian houses surrounding the pool on its three sides. It really comes to life once a year when the Canalway Cavalcade festival (see news pages) held by the Inland Waterways Association since 1983 sees the pool packed with boats and attracts thousands of visitors.

Incidentally, the ‘Canalway’ part of the festival’s name comes from the opening up of London’s towpaths under that name – it’s odd to think that the off-road route through the capital, popular with walkers and (sometimes at commuter times a little too popular) with cyclists, was until the 1970s a no-go area that the public were discouraged from visiting.

A detour to Paddington Basin

Cruising across the pool from the toll house, boaters have a choice: for the Regent’s Canal to Limehouse, bear left to pass to the north side of the island. But first, it’s worth taking the alternative of bearing right along the south side of the pool for the short dead-end cruise (technically outside the scope of this article!) along the final length of the Paddington Arm to Paddington Basin where there are visitor moorings. This is set in canyon-like surroundings between striking modern office developments, and boasts two novel lift-bridges – the Rolling Bridge and the Fan Bridge – which can be seen opening and closing at noon on Fridays.

Incidentally, on the subject of moorings, it isn’t always easy to find anywhere to stop on the Regent’s, as there are many boats moored along the towpath side. One possibility if you’re keen on spending time in London is the pre-paid bookable moorings on the east side of the pool at Little Venice – see the Canal & River Trust website for details. Alternatively, there are 7-day visitor moorings just west of the pool, but note that narrowboats should not moor more than two abreast (and widebeams shouldn’t breast up) here.

Going underground

And so we finally leave Little Venice for the Regent’s Canal ‘proper’ via another bridge with former toll-house which leads via a straight and increasingly deep cutting to Maida Hill Tunnel, its portal unusually topped by a café with views over the canal.

Approaching Maida Hill Tunnel from the west

The tunnel is notable for a quirky historical tale, and a rather more practical consideration. The quirky tale is that the soil excavated from the tunnel construction is said to have been reused to level the site for the third Lord’s Cricket Ground, which was being created (on its present site) as the canal had cut through part of the second ground. And the practical consideration is that this is a wide canal which is frequently used by broad-beam craft, and therefore that even though the tunnel is over 14ft wide, narrowboats should not enter if there is anything coming the other way.

There’s no towpath through the tunnel, but walkers can easily follow the route through the streets to the eastern portal.

As you emerge from the 272 yard bore, look up and you’ll see a large and rather ugly metal trunking which emerges from the towpath surface and disappears into the head wall above the tunnel portal. This is part of a 1970s scheme which took advantage of the almost unused canal towpaths through central London as a route to bury high voltage electricity supply cables, saving the cost of digging up the streets, and using canal water to cool the cables. You’ll notice the concrete slabs forming the towpath surface all the way to East London.

A second and very short tunnel, Lisson Grove (or Eyre’s) Tunnel, this time complete with towpath, features a house built into its eastern portal (built in 1906 for a canal manager), and emerges into Lisson Wide. This former railway interchange basin serving Marylebone Station’s goods yards is now an attractive residential mooring site. It’s followed by a bridge carrying the passenger lines into Marylebone Station and the Underground’s Metropolitan Line, popping out of tunnels on one side of the canal to disappear underground again on the other side. This is the first of several railway crossings on the approach to various London terminus stations, which coped with crossing the canal in different ways.

Through the park

Ahead lies Regent’s Park, built at the same time as the canal (they’re both named in honour of the future King George IV, who was Prince Regent from 1811 to 1820) – and as originally planned it would have run right through the park. In the event, aristocratic fears concerning the behaviour of the uncouth barge crews led to it being diverted around the perimeter, resulting in the tight turn at each end of this length.

It’s an attractive and interesting length around the north side of the park. It passes opulent Nash houses (some original, some built relatively recently to original plans); London Zoo with its own waterbus stop, exotic creatures visible from the water, and former aviary now re-purposed as the zoo’s monkey house; and ‘Blow-up Bridge’. This cast iron structure, more properly known as Maccesfield Bridge, was destroyed when a gunpowder barge exploded under it in 1874. The cast iron columns were salvaged and the bridge was rebuilt, but they were re-erected the opposite way round to even out the wear on the ironwork from the ropes of horse-drawn boats. Look carefully and you can see the original grooves worn on the back of the columns, where no towropes would now pass.

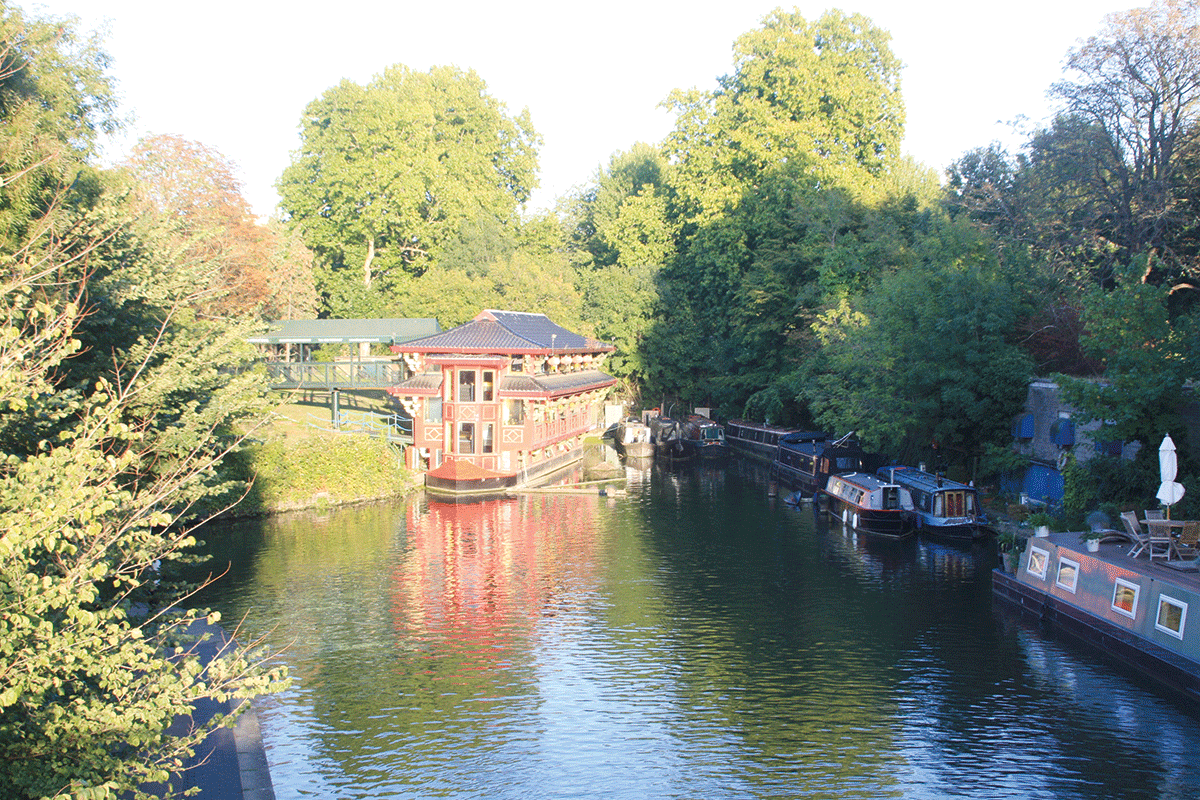

The rather unlikely looking Chinese restaurant at Cumberland Turn

An improbable-looking ‘floating’ Chinese restaurant occupies a prominent place in a short dead-end basin (which is all that remains of the former Cumberland Arm, leading down to a terminus near the Euston Road) as the canal leaves the Park behind and heads for Camden. Trains serving Euston Station and the West Coast Mainline cross on another railway bridge – this bridge marked the top of a steep incline from Euston which trains were originally hauled up by rope. Look out for the castellated walls of the Pirate Castle youth activities centre (and the matching castellations of the electricity sub-station building on the opposite bank), then the iron towpath bridges (see Cruise Guide Extra, page 54) marking our approach to Camden Lock.

The descent begins

There is no lock called Camden Lock. However, there is a famous and eclectic market of that name, a major London attraction, which has spread over an increasing area to the north of Hampstead Road Locks.

Hampstead Road Locks, Camden, mark the end of the long level and the start of the descent to the docks

SEE ALSO – Camden Lock Market

From a weekly craft market with a handful of stalls which began almost 50 years ago, the market has expanded to fill the former canal boat stable buildings and surroundings on the north side of Hampstead Road Locks. Its stalls are renowned for their cosmopolitan image, selling crafts, clothing, bric-a-brac, and fast food.

From a weekly craft market with a handful of stalls which began almost 50 years ago, the market has expanded to fill the former canal boat stable buildings and surroundings on the north side of Hampstead Road Locks. Its stalls are renowned for their cosmopolitan image, selling crafts, clothing, bric-a-brac, and fast food.

Note ‘locks’, not ‘lock’. Every lock on the canal was duplicated side-by-side. This wasn’t particularly rare (other examples include the Cheshire locks on the Trent & Mersey and Hillmorton on the Oxford) but what was unusual was that on the Regent’s it was done from the very start in anticipation of heavy traffic, rather than added in response to congestion. But another less welcome feature was that the locks lacked overflow weirs, necessitating the employment of lock keepers at each lock or flight to regulate the water levels. As a result, following the ending of most commercial freight traffic, one out of each pair of locks was taken out of service and converted into an overflow, with the exception of the top pair at Hampstead Road. Here, the heavy trip-boat traffic (there are at least five regular operators on this length of canal, plus restaurant boats) in addition to the regular through traffic justifies keeping both locks in use.

St Pancras: railways and a cruising club

Two more locks follow in rapid succession, then the canal winds through Camden to reach St Pancras. The former Midland Railway main line crosses on a bridge on the approach to St Pancras Station, and this time the railway builders solved the problem of the awkward height of the canal by building the platforms at high level and using the space underneath as storage for (among other things) beer brought down from Burton. Today you can watch Eurostars pass over the bridge.

Adjacent to St Pancras Lock is the former railway interchange basin which is home to St Pancras Cruising Club, well-known for organising Thames tidal convoys (open to everyone) which are an excellent way for boaters to make their first trip on the tideway. The basin’s been a home to leisure craft for a long time: a vintage sign still proclaims “British Waterways Board St Pancras Yacht Haven”. On the same site a historic former water tower for supplying steam locomotives has been relocated (it was in the way of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link), now forms part of the Cruising Club premises, and is occasionally open to the public.

SEE ALSO – Camley Street Natural Park

This urban nature reserve below St Pancras Lock is a two-acre oasis amid central London’s modern developments. Its habitats include wetlands, meadow and woodland, attracting insects, amphibians, at least six species of mammal, 300 plants, and marsh nesting birds including reed bunting, coot, moorhen and warbler.

This urban nature reserve below St Pancras Lock is a two-acre oasis amid central London’s modern developments. Its habitats include wetlands, meadow and woodland, attracting insects, amphibians, at least six species of mammal, 300 plants, and marsh nesting birds including reed bunting, coot, moorhen and warbler.

Further signs that this is a redeveloped former industrial area include a set of gasholders re-sited and incorporated into modern developments, then after passing Camley Street Nature Reserve (see inset) the canal enters an area of massive recent regeneration on what was once extensive coal sidings connected to King’s Cross Station.

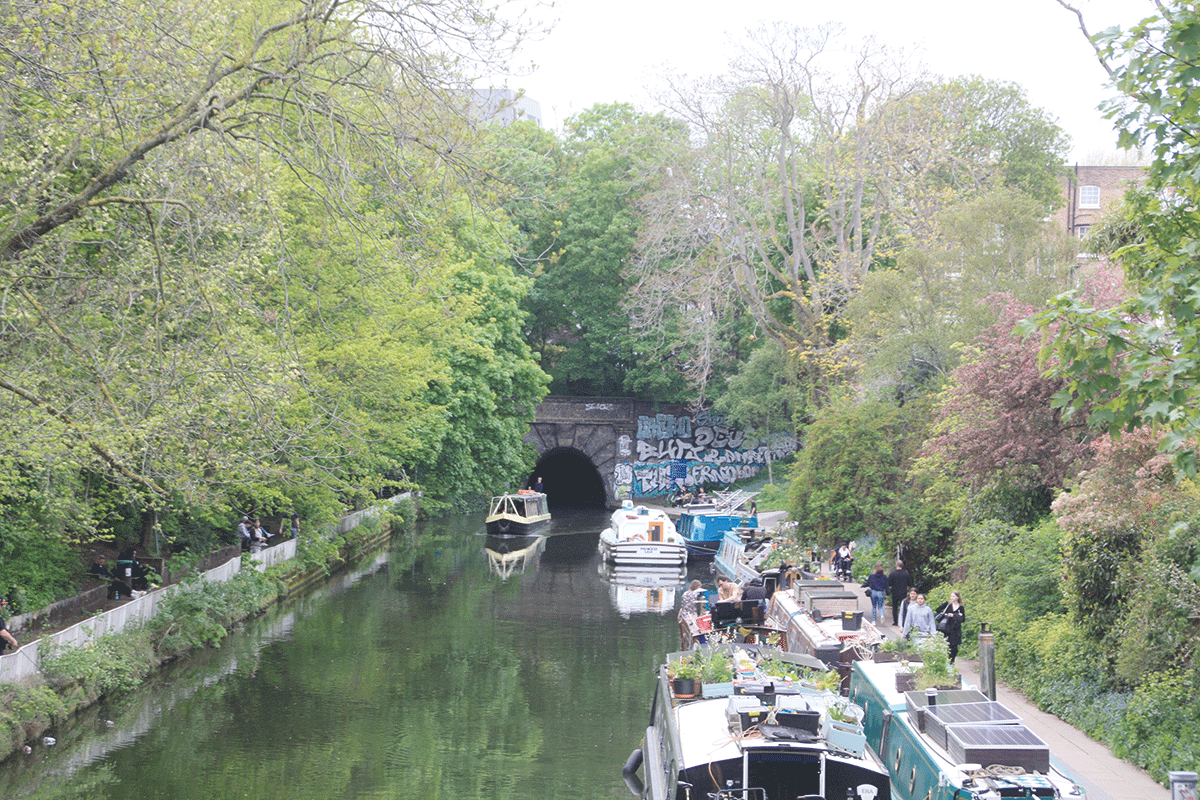

The approach tracks to King’s Cross found an alternative way to cross the canal, burrowing under it in a tunnel, while soon after passing Battlebridge Basin and the London Canal Museum (see inset) the canal itself dives underground again in the 960-yard Islington Tunnel.

Leaving the 960-yard Islington Tunnel

MUST SEE – London Canal Museum

Set in a former ice warehouse sandwiched between modern developments on Battlebridge Basin, the museum tells the story of the capital’s canals and the trade they carried, with exhibits including the rear half of a working narrowboat with boatman’s cabin and one of the unusual towpath tractors which hauled barges in the 1960s. There’s also a display on the ice trade which the building was used for in the days before refrigeration.

Set in a former ice warehouse sandwiched between modern developments on Battlebridge Basin, the museum tells the story of the capital’s canals and the trade they carried, with exhibits including the rear half of a working narrowboat with boatman’s cabin and one of the unusual towpath tractors which hauled barges in the 1960s. There’s also a display on the ice trade which the building was used for in the days before refrigeration.

Islington and Hoxton

This too is a one-way tunnel, so check that it’s clear before entering. It also lacks a towpath, but for walkers there’s a waymarked route (using small plaques set in the pavements) through the streets above, and it passes through a good street market.

As you emerge into a leafy cutting, on the left are the first of what are planned to be a number of ‘eco-moorings’ in London – temporary moorings with electricity supplies, and a ban on running engines, generators and solid fuel stoves.

An old chimney reminds us Hoxton was once an industrial area

The descent towards the docks resumes with two more locks, as the canal passes Wenlock and City Road basins. This was once an industrial area – there are a couple of surviving chimneys, both with a distinct lean to them (perhaps if Little Venice merits its name, this could equally be ‘Little Pisa’!) – but now it’s become a desirable area to live in.

As Islington merges into Hoxton and Haggerston, the towpath which 40-odd years ago was a no-go area now has several cafes and restaurants facing directly onto it.

To the East End

A one and a half mile gap between locks ends at Acton’s Lock, as the canal begins to bend southwards for the descent towards the docks. Briefly living up to the stereotypical urban canal scene as it passes Bethnal Green Gasworks’ impressively large gasholders (as yet unconverted for residential use), the canal undergoes another transformation as it enters Hackney and comes alongside Victoria Park. Less well-known than Hyde Park and Regent’s Park, ‘Vicky Park’ has provided green space for generations of East End folk, and makes an attractive length of canal today. A towpath bridge on the left marks the (slightly awkward in a 70-footer) entrance to the Hertford Union Canal, a handy shortcut for boats heading for the rivers Lee and Stort. Its mile-long dead straight course drops through three locks as it follows the south side of the Park and enters the Lee amid a mix of old industrial buildings, legacies of the 2012 Olympics, and modern craft breweries and the like at Hackney Wick.

Approaching the awkward turn under the towpath bridge into the Hertford Union Canal

Meanwhile, the Regent’s Canal heads southwards, Victoria Park being followed by the much more recent Mile End Park, largely created from derelict land and extending along the east bank for over a mile, including the remarkable ‘green bridge’ carrying the park over Mile End Road.

Going to the docks

Four locks complete the canal’s descent towards the river, the final lock (Commercial Road Lock) opening into Limehouse Basin, as Docklands Light Railway trains rumble over the former main line railway viaduct overhead.

With the Docklands Light Railway above, a boat leaves Commercial Road Lock to enter Limehouse Basin

This was once the Regent’s Canal Dock where ships would transfer their cargoes into dozens of pairs of working narrowboats for the onward journey to the Midlands. Today, the rather smaller reconstructed basin is home to a marina but (despite some controversial proposals to turn more of it over to paid-for moorings) retains some visitor mooring space, useful for craft planning the adventurous Thames tideway trip through central London to Brentford or Teddington and needing to await suitable tidal conditions.

That isn’t the only route out of Limehouse Basin; from the east side of the basin the Limehouse Cut provides another route to the River Lee, and to the curious Bow Back Rivers network of former mill channels and tidal creeks.

And finally, it’s an excellent place to moor up and explore East London, take the Light Railway into the City, or visit one of several popular riverside pubs.

BOATERS’ NOTES

Locks: the upper two locks at Camden plus St Pancras Lock are inaccessible from the towpath without a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key to open access gates.

Tunnels: The tunnels on the canal are regularly used by wide-beam craft with no booking system (unlike the tunnels on the Grand Union Main Line), so make sure there is nothing coming the other way before entering.

The tidal Thames: boaters considering arriving on or leaving the Regent’s Canal via the Thames at Limehouse Basin (for example as part of a ‘London Ring’ cruise) should be aware that the tidal trip through central London is a journey not to be taken lightly, with fast tidal currents on a waterway busy with tripboats, waterbuses, commercial freight vessels and other large craft. However it can be tackled safely in inland craft which are appropriately equipped and reliable, with experienced crew, in suitable conditions, and with adequate planning regarding tidal times (and locks which may need to be booked) and knowledge of the river. An ideal way to experience it for the first time is to take part in one of St Pancras Cruising Club’s annual tideway cruises. The Club also publishes a tideway guide aimed at canal boaters.

As featured in the July 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the July 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here