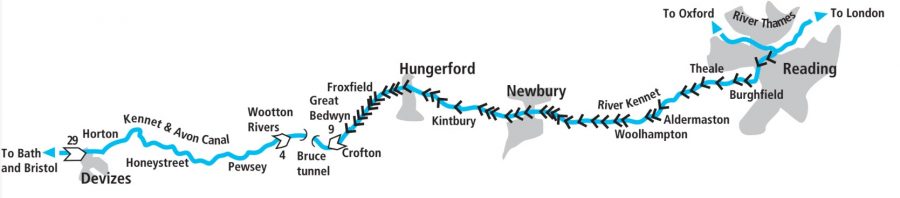

In the first part of our two-part guide to the great through route across southern England, we follow the eastern length from Reading up the Kennet Valley and then through the peaceful Vale of Pewsey to Devizes

The name ‘Kennet & Avon Canal’ is often used these days to refer to the entire route stretching west across the South of England from the junction with the Thames in Reading all the way to Bristol Docks. And we are covering the entire route in this article and the second part covering the western lengths. But historically the route was built as three separate waterways: two river navigations and one canal. And this is still evident today, with river sections at both the eastern and western ends of the route, as well as differences between the locks on the different lengths.

Leaving the Thames at Reading

So we’ll leave the Thames via an unprepossessing entrance under a railway bridge (it used to be overlooked by the town’s gasworks, which didn’t improve the view) a little way east of Reading town centre, and enter what was opened in 1723 as the River Kennet Navigation. This river-based waterway climbed via 21 locks from Reading to Newbury.

County Lock in Reading – note traffic lights just beyond

It was built to take rather larger vessels than can use it today. You’ll appreciate his as you pass along the attractive Kennet Side (with a couple of waterside pubs) to reach the first lock, Blake’s Lock, which still retains its original dimensions of 109ft by 17ft. It also has the odd distinction of being run by the Environment Agency’s Thames division – the changeover to the Kennet & Avon Canal Trust jurisdiction occurs a short distance beyond the lock. In practice there’s no real difference – unlike the nearby locks on the Thames it isn’t keeper operated or powered. But the paddles are operated with a spoked wheel, rather than needing a windlass.

Above the lock is a junction: you can either go straight on, or for an alternative view of Reading (and access to visitor moorings) you can turn right. This leads into a series of backwaters called the Forsbury Loop, rejoining the main route after a few hundred yards.

Look out for a set of traffic lights ahead. These control a narrow and winding length of channel running through what is now the Oracle shopping centre, but is traditionally known as Brewery Gut. It was straightened considerably when the shopping centre was built – coming downstream there used to be an awkward turn into the low stone arch inappropriately named ‘High Bridge’. But can still require care especially when travelling in the downstream direction if the flow of the river has increased following heavy rain. Come alongside the traffic lights and reach out to push the button – unless a boat is coming the other way, they will normally immediately change to green.

Out into the countryside

The traffic light controlled length ends at the approach to County Lock (with slightly inconvenient landing stages and a weir alongside it, requiring a little extra care), following which another winding river section leads past the backs of houses and out of Reading. This leads to Fobney Lock, which also takes a little care as a result of the slightly awkward weir stream entering the channel right by the lock landing stage.

So far the waterway has been based on the natural course of the River Kennet, but once Reading is left behind it starts to make use of some lengthy lock cuts. In places you won’t see the river for some miles.

A busy scene at Aldermaston Wharf

Odd locks

Locks come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Originally they were turf-sided and built to the original 109ft by 17ft dimensions, but some were rebuilt as conventional brick chambers during the waterway’s working life. In some cases they were also reduced in size to match the locks beyond Newbury. However many remained in their original form until the waterway went out of use and fell into dereliction around the 1950s.

Come the restoration of the route, led by the Kennet & Avon Canal Trust from the 1950s to the 1990 reopening, the remaining turf locks presented restorers with a problem. The then navigation authority British Waterways was unwilling to see them restored with the original sloping earth banks. But there was a feeling among some canal supporters that it would be wrong for a once common but now rare and historic lock type to become extinct. In the end, the majority were rebuilt in masonry – some retaining their scalloped edges – but two were kept as turf locks.

Monkey Marsh, one of two remaining turf-sided locks on the Kennet

So now we have a mixture of normal chambers (large and normal sized), a couple of large ones with scalloped edges, a large turf lock and a normal size turf lock.

This is all very interesting to those who like waterways heritage, but of rather more practical use is the knowledge that the locks which were reduced in size are quite tight for length. I know from personal experience that they will take a 71ft 6in former working narrowboat, but only just. Getting out of a lock when heading downhill involves opening the opposite side gate first and then pushing the bows across.

Burghfield village with its handy waterside pub is followed by Garston Lock (one of the surviving turf locks) and Theale, whose useful shops are a short walk to the north from Theale Bridge. This introduces another Kennet & Avon speciality – swingbridges. These range from simple wooden footbridges opened by hand using a balance beam to some quite busy road bridges operated electrically with a CRT key, as is the one at Theale. At Tyle Mill Lock the road swingbridge is so close to the lock that (unless your boat’s very short) you’ll need to have the lock ready before you open the bridge. At Aldermaston the bridge carries a main road: it only operates between sunrise and sunset, and boaters are requested not to use it on weekdays between 8am and 9am and between 4.30pm and 5.30pm. And finally, Woolhampton Lock is approached via a swingbridge followed by a sharp bend with an appreciable current: if you’re going upstream, get the lock ready before you open the bridge; going downstream, open the bridge before you leave the lock.

But please don’t be put off if this sounds like hard work or worry. The Kennet is a very pleasant waterway climbing westwards up a broad valley through rural Berkshire, passing attractive villages on the way.

The second surviving turf lock at Monkey Marsh marks the approach of Thatcham. This in turn leads on to Newbury, a busy market town with the waterway passing through its centre. A sign near the town bridge still warns boat captains that they will be fined if they allow their horses to haul across the street. It wouldn’t be so bad now that it’s pedestrianised, but I can imagine it would have been more of an issue when it carried the A34 main road. Incidentally you may actually see a horse boat on the next section, as horse-drawn public trips are operated by a boat based at Kintbury.

Off the Kennet, onto the K&A ‘proper’

Newbury, where the Kennet Navigation becomes the Kennet & Avon Canal

Newbury was historically the terminus of the Kennet Navigation, and from here onwards we’re on the Kennet & Avon Canal ‘proper’. Opened in 1810, this ran for 57 miles via 79 locks, climbing from the Kennet at Newbury to a summit level in the Berkshire Downs before descending to Bath. There it met the Bristol Avon which was already navigable to the Severn Estuary, completing the east-west route across southern England. It too fell into dereliction in the early 1950s, but was restored in stages culminating in the 1990 reopening to through navigation.

Unusual skew swingbridge at West Mill, Newbury

Having said that, there isn’t any obvious change in the nature of the waterway – other than that the locks from now on are a fairly uniform shape and size (and slightly tight for full-length narrowboats, as described above). In fact the changeover from river to canal is a very gradual one. We already mentioned that the Kennet Navigation between Reading and Newbury featured some canal cuts up to several miles long; conversely the first few miles of the Kennet & Avon Canal include a few sections where part of flow of the River Kennet merges with the canal channel, meaning that currents can still be experienced after heavy rain.

A quiet stretch approaching Kintbury

By the time Kintbury – a quiet village with a canalside pub – is left behind, river and canal waters have parted for the last time. The canal continues to follow the Kennet valley, climbing through a succession of locks at intervals of a mile or so, accompanied by water meadows, woodlands and commons. The A4 main road mostly keeps its distance, but the busy West of England main line railway keeps company with the canal.

Climbing to the summit

Moorings in Hungerford town centre

After Hungerford, another pleasant and useful market town, the climb begins to steepen as the canal approaches its summit. Watch out for the swingbridge across the chamber of Hungerford Marsh Lock – unless your boat’s very short it will need to be opened before using the lock.

Locks become more frequent west of Hungerford

The locks continue through Froxfield, Little Bedwyn and Great Bedwyn villages, as the canal climbs the valley of the little River Dun. The final nine locks form the Crofton Flight, passing between Wilton Water on the left and Crofton Pumping Station on the right.

Canal and railway run parallel though Bedwyn

Crofton Top Lock marks the beginning of the summit level, with a cutting leading to the 502-yard Bruce Tunnel. This was named after landowner Thomas Brudenell-Bruce, the 1st Earl of Ailesbury (yes, spelt like that!) who refused to let the cutting continue through his land, insisting that a tunnel be built to hide the canal from his sight. It’s a sign of the times that not only did the canal company also have to name the tunnel after him, but they also put up a plaque “in testimony of the gratitude for the uniform and effectual support” of the Earl for letting them build their canal at all. The tunnel is occasionally also referred to as Savernake Tunnel, taking its name from the forest just to the north with its network of footpaths and drives.

Walkers will need to deviate from the canal as there’s no towpath through the tunnel – there’s an easily followed footpath over the top. Meanwhile for boaters there’s only a brief respite from locks, as the summit level is a mere three miles long, another lengthy cutting leading from the tunnel’s western portal to Wootton Rivers top lock.

Climbing Wootton Rivers locks

On to the Long Pound

The four well spaced-out locks lower the canal gently to Wootton Rivers village (with a pub a short walk from the canal), and then boat crews finally do get a rest. This is the start of the Long Pound, 15 miles of rural waterway which meanders its way through the Vale of Pewsey almost entirely free of main roads, railways or any other interruptions of the peace and quiet.

Pewsey Wharf, canal settlement with restaurant

In fact although it may seem remote, you don’t have to walk far from the canal to reach civilisation. Pewsey town’s shops are three quarters of a mile to the south (Pewsey Wharf is a separate little settlement with a canalside bar and bistro), while All Cannings and Bishop’s Cannings villages are also within walking distance, and the tiny village of Honey Street is actually on the canal.

A typically quiet and remote length of the Long Pound near Honey Street

Keep a look out for the white horse carved in a chalk hillside to the north at Honey Street, moor up and walk into All Cannings to visit the Long Barrow – a modern construction based on prehistoric burial mounds that are common on the Downs near here – and watch out for a few interesting canal features.

Curious metal suspension bridge on the Long Pound

These include Stowell Park Bridge (a spindly metal suspension bridge carrying a footpath), and the ornate Lady’s Bridge and adjacent lake-like length of canal known as Wide Water. These were created by the canal’s builders to improve the view for the landowner Lady Susannah Wroughton, in addition to them paying her £500 (at least she didn’t insist on a tunnel!)

Swingbridges are a feature of the canal: this one hasn’t swung for a while

And while the crew might not have any locks to work, they don’t get off scot-free – there are a couple of swingbridges to open.

A long cutting marks where the canal passes out of the Vale of Pewsey and into the catchment area of the Bristol Avon.

Towards the west end of the Long Pound near Bishop’s Canning

A sharp right bend is followed by a straight length leading into the centre of Devizes – where the Long Pound comes to a very abrupt end at the famous Caen Hill Locks. It’s an interesting and historic market town, with a canal museum, the Wharf Theatre, the Wiltshire Museum and Wadworth’s Brewery among its attractions. It’s a good place to pause, so it’s where we’ll end the eastern part of our cruise guide – click here to continue along the western section including the descent via the spectacular Caen Hill Locks into the Avon Valley and on to Bath, the River Avon Navigation and Bristol.