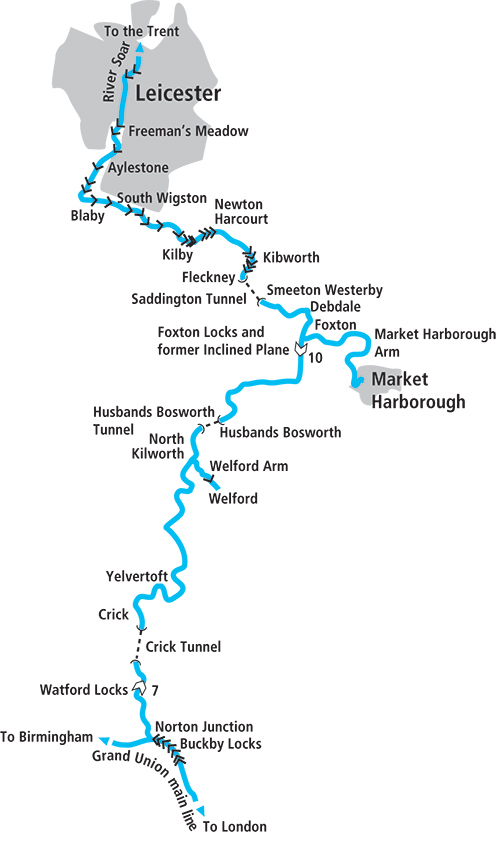

In the first part of our two-part guide to the route linking the Grand Union Main Line to the Trent, we climb to the rural and at times rather remote summit level, before descending via the famous Foxton Locks flight to reach Leicester city.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

Today’s boaters tend to think of the Leicester Line (or Leicester Section) of the Grand Union Canal as one waterway – or perhaps two. There’s the canal length running northwards from the main line of the Grand Union at Norton Junction to Leicester, then the River Soar part continuing northwards from Leicester downstream to the River Trent at Trent Lock. But historically it was built as four separate waterways.

Today’s boaters tend to think of the Leicester Line (or Leicester Section) of the Grand Union Canal as one waterway – or perhaps two. There’s the canal length running northwards from the main line of the Grand Union at Norton Junction to Leicester, then the River Soar part continuing northwards from Leicester downstream to the River Trent at Trent Lock. But historically it was built as four separate waterways.

And in following it northwards from Norton Junction to the Trent, we’re actually cruising it back-to-front in historical terms. We’re starting with the last section to be built, and as we arrive at Trent Lock in the second part of this article in the December issue, we’ll be cruising on the first part of the route to be opened.

A complex history

This complex history makes for some contrasts in the styles of the different lengths of this attractive East Midlands waterway, as well as explaining one or two oddities as we cruise along the route. And one of those oddities which becomes apparent almost immediately is the different sizes of boat that the route’s different component waterways were built for.

The London to Braunston section of the Grand Union Main Line was originally built as the Grand Junction Canal, with locks big enough to take a 70ft by 14ft widebeam boat, or a pair of narrowboats side-by-side. But if you took the turn (quite a sharp one if you’re coming from the Braunston direction) into the Leicester Line at Norton Junction in a widebeam, you wouldn’t get very far. Yes, the bridges are all wide as you cruise northwards along the first two gently meandering route miles through the rolling landscape that characterises the canals of this area, but then the canal arrives at the seven-lock Watford flight – and they’re built for narrowboats of around 7ft beam.

Considering that the length from Norton to Foxton was the very last section of the route to be built, only opened in 1814, building narrow locks may seem a shortsighted move. But by the time it was built, even on the widebeam Grand Junction Canal, narrowboats were carrying most of the traffic. Indeed, at one time the canal company banned widebeam boats from Braunston and Blisworth tunnels, because it meant operating a one-way traffic system which created a bottleneck, whereas narrowboats could pass each other underground. Which must have been an interesting manoeuvre in the days of horsedrawn boats being ‘legged’ through tunnels without towpaths. But I digress…

Staircase locks with a difference

Whatever the rights and wrongs of their width, they’re an attractive flight, and they’ve got one very interesting feature – which boaters need to be aware of. Four of them are built in the form of a staircase, with each lock leading directly into the next one – but it’s a staircase with a difference. Instead of the bottom paddles of each lock emptying directly into the next one below it, there are two different paddles – one painted red, and one painted white. The white one empties the upper lock into one of a set of ‘side ponds’, small reservoirs adjacent to the locks, while the red one fills the lower lock from the same side pond. This means that unlike a ‘normal’ staircase, you can empty a lock even if the one below it is full, and you can fill a lock even if the one above it is empty. In effect, it means that the flight operates more like a set of individual locks, rather than a staircase, which saves water.

Leaving the four-lock staircase at Watford

But don’t worry if this sounds complicated – there will be lock keepers on hand, and as regards the order of opening the paddles, remember “Red before white – you’ll be all right”!

The locks are in an attractive setting, but not a terribly peaceful one: the M1 motorway is on one side, and the A5 trunk road and West Coast Main Line railway are on the other. There’s a reason for this: there’s a gap in the hills (yes, the ‘Watford Gap’ that gave it name to the motorway service station) which each successive set of transport planners have taken advantage of, from the Romans building their road connecting Dover and London with the Midlands to the motorway planners of the 1950s – and canal engineer Benjamin Bevan did the same.

Oh, just one final point before we go further: I haven’t mentioned the original name of the canal from Norton to Foxton – largely because I’ve been putting it off, to avoid confusion! It was actually called the Grand Union Canal: the original use of that name, well over a century before the same name was reused for the great waterways amalgamation of the 1930s which brought the entire routes from London’s docks to Birmingham and the Trent under a single ownership.

On the quiet summit level

We’re now on the Leicester Summit: the railways and main roads are soon left behind and we’re winding our way along 20 miles of lock-free meandering route, twisting and turning through quiet countryside to skirt the hills of Northamptonshire and Leicestershire. And where it can’t go around them it goes through them: we soon reach Crick Tunnel, at 1528 yards the longest of the three on the route to Leicester. Like those on the Grand Union Main Line, it was built to take craft up to 14ft wide (as were all the bridges, so that in the event that the canal company chose to widen its route, only the locks would need rebuilding) but as it never saw any boats wider than 7ft, it’s always been possible for boats to pass each other inside the tunnel.

There’s no towpath, but for walkers there’s a route over the top following local roads and footpaths rather than a purpose-made ‘tunnel path’ as found at some tunnels.

The tunnel emerges close to Crick village, an attractive and useful village with several pubs and shops, where the canal comes to life once a year in late spring for the Crick Boat Show hosted at the marina.

Passing Yelvertoft village

Yelvertoft, like Crick, is a little way away from the canal (but within easy walking distance) – in fact there are very few villages actually on the waterside. Partly this reflects the terrain, the canal’s engineers sticking to the contour through the hilly countryside to avoid unnecessary earthworks (rather like some much earlier contour canals like the southern Oxford Canal); it may also reflect the fact that this route was built primarily as the last missing link in a through route, rather than to serve the local area. But partly it’s just that it’s rather quiet countryside and has become more so – there’s the site of an abandoned mediaeval village alongside the canal as it skirts Hemplow and Downton hills.

Kibworth Top Lock: from here onwards the locks are wide-beam, so narrowboats can share

One village that the canal does serve is Welford, via an arm a mile and a half long, complete with one lock. The reason for this is that the reservoirs which keep the summit level topped up with water are in the valley of the upper Avon (yes, the Stratford one) beyond Welford, and the arm is in fact a navigable feeder. It’s worth cruising to visit Welford’s shops and pubs (including a curious castellated one by the canal basin) as well as the boaters’ facilities block by the terminus.

Continuing north eastwards, the canal skirts two more villages, North Kilworth and Husbands Bosworth, the latter being reached by footpath from the north east portal of the 1166-yard Husbands Bosworth Tunnel. The final miles of the summit are rather less winding than the previous lengths, as the canal makes for Foxton where the long level pound comes to an abrupt end…

At the terminus of the Welford Arm

Foxton Canal Museum

Housed in the re-created boiler house for the steam engine that powered the former Inclined Plane boat lift (see Cruise Guide Extra, page 54), the Foxton Inclined Plane Trust’s museum tells the story of the locks and lift with a working model and audio-visual displays. And outside the museum, you can explore the preserved remains of the lift itself

Sudden descent at Foxton

In one of the country’s steepest flights, the two five-lock staircases (separated by a short passing pound) descend 75ft in a very short distance. They make an impressive sight, and have become a popular local attraction. Like the Watford staircases they’re built with side-ponds (remember, “Red before white…”) and there are usun lly keepers on duty. When you arrive, check with them before you enter the first lock. At busy times you may have to queue, but there’s plenty to see while you’re waiting – the remains of the former Inclined Plane, the museum, plus two pubs by the bottom lock and rather good ice cream on sale at the top lock cottage.

On leaving the bottom lock, boats arrive at a T-junction, with the five-mile dead-end Market Harborough arm to the right, and the through route to Leicester to the left. And this is where the old Grand Union Canal ends, and we enter an older canal which forms the next part of the Leicester Line.

Steep descent: the ten staircase locks at Foxton

Armourgeddon Military Museum

On the A5199 about a mile’s walk from the east end of Husbands Bosworth Tunnel is this museum with whose exhibits include tanks, military vehicles, guns, cannons and militaria from the First World War, Second World War and Cold War. You can see the tanks driving at weekends and selected Wednesdays

An older canal

This was the Leicestershire & Northamptonshire Union Canal (also known as the Old Union Canal), although it doesn’t actually reach Northamptonshire. This is a clue to its history: it was intended to reach all the way from Leicester to Northampton, where boats would join the Northampton Arm and reach what’s now the Grand Union Main Line at Gayton Junction. But money ran out when it had only reached Market Harborough, and (as we’ve seen) the eventual through connection took a different route.

It’s well worth turning right for the five miles cruise to Market Harborough, an attractive market town with useful shops, before returning to Foxton and continuing north.

Although the canal continues its meandering way through the hilly countryside, you might soon notice another clue that you’re on what was historically a different waterway, as you start to see a few wide-beam craft. Yes, this earlier part of the route was built for 14ft wide craft. In fact, Foxton and Watford locks are all that prevents boats wider than 7ft from getting between the broad-beam networks of the north and south of the country, as from here northwards it’s wide locks all the way to Yorkshire and across the Pennines into Lancashire. But before we meet the first of these locks, we’ve got another tunnel. Unlike the previous two, Saddington (880 yards) does see the odd wide-beam boat. However, these only travel by booked passage in the early morning with the tunnel closed to traffic in the opposite direction; otherwise if you arrive in a narrowboat you can enter without fear of meeting something that you can’t pass. The wide locks begin at Kibworth with a spread-out flight of five, followed by seven more at Newton Harcourt. Meanwhile the canal passes Smeeton Westerby, Saddington, Newton Harcourt, Fleckney and Kilby villages, once again all set back a little way from the waterway.

Descending the seven locks at Newton Harcourt

Descent into the Soar Valley

By Kilby Bridge with its well-known canalside pub, the hilly country is gradually being left behind and the canal is descending towards the River Soar valley. It’s also leaving the quiet and sometimes quite remote countryside and approaching the outer reaches of the Leicester built-up area. However, you wouldn’t always know it: for much of the way into the city there are open fields or meadows on at least one bank of the canal, as developments keep their distance from the Soar and its tributary the River Sence. There’s a reason for that: The Soar does have a tendency to flood after heavy rain, and although we won’t be joining the River Soar section of the Leicester Line until the centre of Leicester, it exerts an influence on the canal before we get there. Locks at regular intervals continue the descent into the valley, and beyond King’s Lock, even though we’re still on a section that was built as part of the Leicestershire & Northamptonshire Canal, the main part of the river’s flow merges with the canal. This means that it can be affected by floods: check the water level gauge below the lock, especially if you arrive during or after heavy rain, to make sure that it indicates that it’s safe to proceed.

Climbing out of the Soar Valley on the north side of Leicester

An industrial area indicates that we’re arriving in Leicester, and a large weir (protected by a boom) at Freeman’s Meadow makes it more obvious that we’re now on a river-based waterway. But the final length as the canal approaches the city centre is much more canal-like and rather impressive straight section spanned by several fine bridges, and provided with secure visitor moorings accessed by Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ key. Known as the Mile Straight, this length was built, and the river diverted, as part of an early flood control scheme.

Near the end of the Mile Straight you may spot the last Grand Junction Canal milepost informing you that it is “0 miles” to Leicester. This was where the Leicestershire & Northamptonshire Canal ended, and once again we’re continuing onto a rather older waterway – and one that we’ll be covering next month in the second part of this article.

As featured in the November 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the November 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here