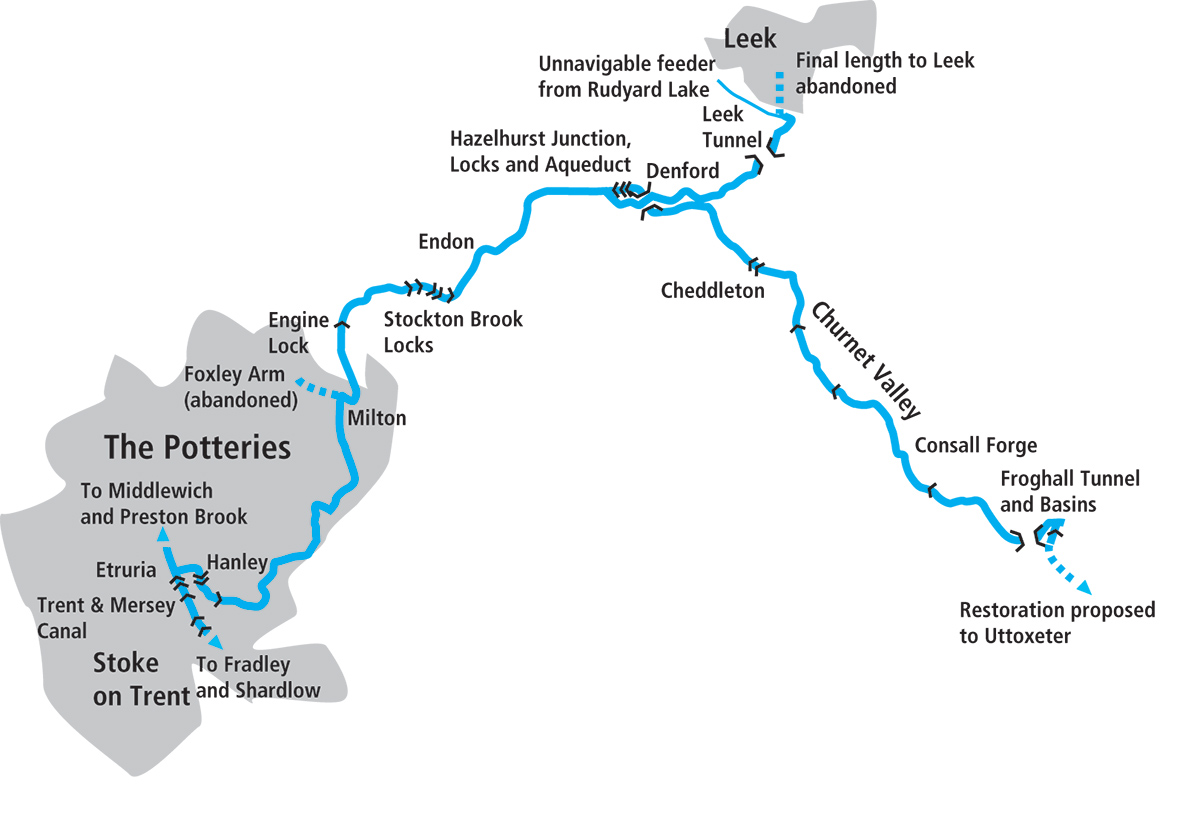

The Caldon Canal packs a huge amount of interest into just 20 miles, with locks, tunnels, aqueducts, industrial heritage and the beautiful scenery of Staffordshire’s Churnet Valley

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

Normally, it would be a great honour to be following in the footsteps of famous canal engineer James Brindley. But perhaps not so much so when it comes to the Caldon Canal. Sadly, when surveying for the route of the proposed 17-mile branch heading eastwards towards the Staffordshire moorlands, the great man got caught out in a downpour, went down with a nasty cold, developed pneumonia and died. And the last two times that I’ve been on a photo shoot for articles about the Caldon Canal, I too have managed to get a soaking from a downpour. I’ve survived them both, but it’s not exactly a good precedent…

Or perhaps it is. Because not only was the Caldon built to tap into useful freight traffic from the limestone quarries around the Churnet Valley to the industries of what’s now the city of Stoke-on-Trent, it was also intended to supply water to its parent waterway the Trent & Mersey Canal. So being in an area with plenty of rainfall isn’t a bad idea. We’ve followed this aspect of the Caldon in more detail in our Cruise Guide Extra on page 53, but in this article we’re concentrating on its attractions as a cruising waterway.

And there are many of them, especially for a waterway which (even when you add the length of the Leek Arm to the main Froghall line) stretches for barely 20 miles. In that short distance it includes tunnels, aqueducts, single locks, flights of locks, staircase locks, lift-bridges, a section of river, and heritage attractions including a watermill and a steam railway. It’s a microcosm of the whole canal network, squeezed into an attractive corner of Staffordshire.

‘Attractions’ perhaps wasn’t a word that would have been used very much when describing the first few miles of the Caldon Canal 30 or more years ago. The route began with a grimily industrial stretch through the heart of the ‘Five Towns’ – the Staffordshire Potteries conurbation consisting of Hanley, Stoke, Burslem, Tunstall, Longton and Fenton (yes, I know, that’s six!) – and waterways guides would encourage you to put up with it for the sake of the completely contrasting rural splendours of the remainder of the canal.

The urban surroundings are starting to be left behind after the first three miles from Etruria

But times have changed. For those coming north on the Trent & Mersey, arriving up Etruria Locks, the canal still begins with a hairpin right-hand turn above the top lock to challenge the steerer of a 70-footer. But where the canal once began amid potteries and their associated works, such as mills for grinding the additives to the clay, it now runs between modern housing surrounded by parkland and green space. A statue of James Brindley overlooks the canal which brought about his demise, and the surviving Etruscan Bone and Flint Mill is a museum (see inset).

Etruria industrial museum

Etruria industrial museum

Like the Cheddleton Flint Mill, this building once produced ground flint (as well as ground bone) for the china industry, but steam powered and on a larger industrial scale. It is now a museum with displays of the mill, its history and its machinery open on Fridays only – and on about four weekends a year, the steam engine is in operation.

A second sharp bend (which was once much tighter) leads under a modern footbridge to Bedford Street Locks, a staircase pair climbing almost 20 feet. The characteristic Trent & Mersey Canal style split bridge over the lock tail reminds us that this was part of the T&M system, as does the tendency of the upper gate paddles to pull a boat forward quite fiercely if opened quickly.

Above the lock is a brief reminder of what this length was once like, as the narrow channel winds its slightly unkempt way between spreading vegetation giving a green tinge to the old but still working brick-built industrial premises surrounding the canal. But scenes like this have been rapidly disappearing in recent years, and soon the canal emerges into more modern surroundings with new housing replacing much of the traditional industry. A couple of the old brick bottle-kilns which typified the Potteries area and its major industry now look rather incongruous, standing amid recent developments, but at least one canalside pottery is still in production – as I was passing it on my photo shoot, I saw an employee carrying out the time-honoured task (which some readers might recall from Wedgwood adverts of the 1970s) of smashing flawed pieces of chinaware and dumping them in a skip!

Passing a third lock (a much shallower one, added later to counter mining subsidence) and an attractive length through Hanley Park, the canal clings to the contour as it follows the side of the valley of the infant River Trent, just a small stream by this point. Ivy House Bridge introduces a Caldon Canal feature, lift-bridges: there are several surviving examples opened by various methods from traditional manual operation to electric power controlled by a Canal & River Trust ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key. Finally, around Milton the built-up area is left behind, and the remainder of the canal is entirely rural.

Climbing the flight of five Stockton Brook locks to reach the canal’s summit level – with an impressive former waterworks pumping station on the right

The deep Engine Lock (named after a nearby mine pumping engine) is followed by a flight of five at Stockton Brook which raise the canal to its summit level. This runs for barely two and a half miles – but once it was even shorter. Hazelhurst Junction (where the Leek Arm turns off to the right) is followed by the three Hazelhurst Locks beginning the descent towards Froghall.

Passing under Hazelhurst Aqueduct which carries the Leek Arm over us from right to left, the main Froghall line bears right as it enters the Churnet Valley, following it downstream through Cheddleton. Look out here for the canalside flint mill (see inset) and the unusual small warehouse straddling the canal, as well as watching (and listening) for signs of life at the Churnet Valley Steam Railway which parallels the canal for the rest of the way.

Churnet Valley Railway

Churnet Valley Railway

Formerly part of the Macclesfield-Leek-Uttoxeter line, the length from Leek Brook to Froghall (accessible from the canal at Froghall, Consall and Cheddleton stations) is operated as a heritage railway with historic steam locomotives and carriages. There are dining trains and even a breakfast train featuring traditional Staffordshire oatcakes

Two more locks in Cheddleton continue the gentle descent. They were the scene of the reopening in 1974, after the campaign led by the Caldon Canal Society resulted in the restoration of the length from Hazelhurst to Froghall which had fallen into dereliction in the early 1960s.

Attractive moorings at Cheddleton

The canal is now following the increasingly scenic Churnet Valley; it’s a secluded largely wooded route, with no roads following the valley at all, and just the steam railway and the little River Churnet for company. After Oakmeadowford Lock, the canal and river combine their channels for a mile or so (see boaters’ notes), a particularly attractive winding length which ends when the two waterways separate at Consall Forge – noted for its station on the steam railway (look out for the platform waiting room shelter which is cantilevered out over the canal) and the isolated Black Lion pub.

Cheddleton Flint Mill

Cheddleton Flint Mill

This canalside complex of two watermills (plus drying kilns and miller’s cottage) was used to produce powdered flint, an important additive used by the pottery industry. It is in working order, preserved as a museum, and open to the public (currently Mon and Wed afternoons)

Just before Flint Mill Lock is a winding hole where full-length boats can turn; any which continue beyond here will need to be able to fit through the low Froghall Tunnel – see boaters’ notes. The canal’s quiet, unspoilt character continues, but there’s the odd clue that it wasn’t always like this, and that there were local industries that the canal was built to serve. At Consall old limekilns are visible, and the curious name of Cherry Eye Bridge (with its unusual pointed arch) isn’t quite as idyllic-sounding and rural as you might think – it’s reckoned to be the name of a medical condition suffered by ironstone miners as a result of rubbing their eyes with ore-stained hands.

The short (and low) Froghall Tunnel emerges into the final length of the canal leading to the Froghall terminus basins – note the plural; since 2005 there have been two of them.

Leaving Flint Mill Lock, the last before Froghall

Froghall too might sound rustic and rural (or perhaps like something from The Wind in the Willows), but was quite an industrial location in its day – a sort of smaller version of the great canal-to-horse tramway limestone interchange at Bugsworth Basin on the Peak Forest Canal. Around the terminus there are still signs of limekilns and the four different incarnations of the tramway connecting to the quarries at Cauldon Low which provided much of the canal’s trade. But at a junction just before the final bridge, a sharp right turn now leads into a restored lock, opened in 2005 along with a second basin below it, as part of the Caldon Canal Society’s Destination Froghall project. There were two parts to this scheme: lowering the water level from Flint Mill Lock to Froghall so that more boats could fit through Froghall Tunnel, and restoring this lock in Froghall and the basin below it to create a better destination for those boaters who took advantage of this. But there’s more to it…

The lock and the basin don’t just form a new terminus for the Caldon Canal. They’re actually the start of the Uttoxeter Canal, a 13-mile extension which continued down the Churnet Valley all the way to Uttoxeter. Much of it must have been just as scenic as the length we’ve navigated from Cheddleton – but sadly it was abandoned as long ago as 1849 and parts of it were used for the (now mostly abandoned) railway line. However, the Caldon & Uttoxeter Canals Trust (the new name chosen by the former Caldon Canal Society to reflect its wider aims) believes it can be restored, and one day boats will cruise these lengths, to a new terminus in Uttoxeter.

The restored lock and basin opened in 2005 to create a new terminus at Froghall – and as the first step towards reopening the Uttoxeter Canal

For now, though, this is where boaters must turn and retrace their steps. Don’t just head straight back to Etruria, though, because the Leek Arm is well worth a visit. Beginning with a sharp left turn at the junction above Hazelhurst Top Lock, the Arm runs along the valley side before turning sharp left and crossing a series of aqueducts over the Froghall line of the canal, a stream, and a disused railway.

It then clings to the contours as it follows the Churnet Valley upstream towards Leek. A curious wide pool leads to Leek Tunnel, 240 yards long and rather more generously proportioned than Froghall. It bears the signs that it was one of several tunnels that required major work in the ‘Tunnels Crisis’ of the 1980s, in the form of a length rebuilt from concrete sections.

Beyond the tunnel there’s just half a mile left before a winding hole where a sign recommends that any boats over 45ft should turn. And that’s because the canal no longer quite reaches Leek: the final mile was abandoned in 1944 and filled in, and the arm ends rather incongruously halfway onto an aqueduct over the River Churnet. CUCT would like to reinstate the final section (as one of them said, they hope to “get the canal to Leek”, which isn’t something you often hear!) But in the meantime it’s only a 20-minute walk into Leek for shops, a selection of pubs, and a mill designed by millwright James Brindley (before he became a canal engineer) and open to the public.

And in case you’re wondering why it ends in such an odd place, well, that and the mention of Brindley takes us right back to the start of the article, and to the canal’s second important function – as a supplier of water to the Trent & Mersey Canal. The Leek Arm survived as far as this point (even though it had been legally abandoned) because this is where an important feeder comes in from Rudyard Reservoir.

Boaters’ Notes

Froghall Tunnel is very low and narrow. There is a gauge at the tail of Flint Mill Lock which indicates whether your boat will fit – it depends on a combination of height and width of the cabin. If it won’t, and your boat is more than about 65ft long (the size of the winding hole just before Froghall Tunnel), and you don’t want to risk having to reverse all the way back from Froghall, you should turn at the winding hole at Flint Mill Lock. Full length boats which fit the tunnel can turn round at the terminus beyond.

Be aware that the river section between Oakmeadowford Lock and Consall Forge is affected by currents and water levels in the Churnet and may be impassible after heavy rain. There is a gauge on the tail of Oakmeadowford Lock: if the water level is in the red section, do not enter the river section.

Some lock paddles are secured using a T-handle (‘handcuff’) anti-vandal key. The lift-bridges are operated by either a CRT ‘Watermate’ (sanitary station) key or a windlass.

As featured in the September 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the September 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here