The Chief Executive of the Canal & River Trust has gone on record warning that the recently announced Government funding contract may be insufficient to keep the whole waterways network open. Canal Boat’s Martin Ludgate spoke to him about how serious the threat is

“Canals at risk”, read the headlines in mid-July. “World Heritage site under threat by cuts”; “The alarming prospect of canal closures”; “Parts of UK canal network likely to close” – and they weren’t just talking about temporary closures for emergency repairs to a system suffering the effects of a shortage of maintenance funding. No, this was the long-delayed announcement of the CRT’s Government funding contract to run onwards from when the current contract expires in 2027 – and the message that the media were picking up from CRT Chief Executive Richard Parry was that the cash on offer from Government department Defra is being reduced so much in real terms that at some point it will be insufficient to keep the Trust’s waterways open and navigable.

Could canals and river navigations genuinely face permanent closure during the 2027-2037 funding period? Canal Boat spoke to Richard Parry on the subject.

Repairs under way at a major breach at Dutton several years ago. Might another such breach on a less busy canal lead to “difficult decisions” about repairing it?

How big a funding cutback?

But first, how deep is the actual cut? The grant has been pegged at £52.6m per year since index-linking ended in 2021, and is set to stay at that rate until the end of the current contract finishes at the end of the 2026-27 financial year. It will then be cut by 5% every year for the ten years of the new contract, ending on just £31.5m in 2036-37.

In total, that means that the waterways will be short of something like £100m over that decade, compared to what they would have received if funding had remained constant. But it’s worse than that. Thanks to recent high inflation, CRT estimates that £31.5m in 2036-7 represents almost a 50% cut in real terms, and that the total loss of money between now and 2037 compared to an index-linked grant keeping pace with inflation is more like £320m. While accepting that the planned funding for 2027-37 would have been “challenging” even with the much lower inflation rates that were the norm until a few years ago, Mr Parry’s view is that recent and current price rises makes it unrealistic.

Traditional wooden lock gates being assembled at Stanley Ferry workshops. Will metal or composite gates be a cheaper alternative?

Any room for manoeuvring?

But how set-in-stone are those figures for future funding? We asked Mr Parry if there was any likelihood of negotiation, given the negative publicity generated by the announcement. His view was that the Waterways Minister was unlikely to phone up saying “We’ve changed our mind”, but that if the level of campaigning is kept up over the next year, it’s “unlikely but not impossible” that there could be any more on the table. A number of MPs of all parties are known to be unhappy with the situation (although as we went to press several on the Government side had already replied to constituents’ letters by taking the Defra view, pointing out that it was under no obligation to provide any cash at all after 2027, and lauding its generosity in providing the cash to help CRT to “full independence” by 2037). Meanwhile, Defra seems happy to spread the word regarding all the benefits of canals in terms of wellbeing, heritage, green infrastructure, economic benefits, nature conservation and more (and the figures from the Government’s own report of over £6 billion a year as the value to the country of those benefits) – but less willing to back it with sufficient money for these benefits to continue.

However, Mr Parry reckons that the most likely opportunity for a reopening of the discussion and a rethink of the figures will come as a result of the next general election.

Temporary balance beam repair: a sign of things to come?

Will it mean canal closures?

But if there’s no change, and the waterways are stuck with the settlement that’s currently on offer, will there genuinely not be enough cash to keep the network open? Mr Parry’s response is clear “We just don’t think it’s possible to sustain the network with the sort of income we would have.”

That’s not to say that the Trust can’t find ways of raising more income elsewhere, or reducing expenditure. As regards the first of those, boaters will already be aware of a consultation under way into increased licence fees simply to keep CRT going under the current fixed annual Defra funding. There’s no consultation on whether they should rise – as far as CRT’s concerned there’s no option but to increase rates at well above the rate of inflation; the decisions yet to be made concern whether the rises will apply across-the-board, or are weighted towards wider craft or those without home moorings. But this is likely to be just the start: Mr Parry told us that fees were “likely to continue to rise” in real terms, although he accepted that it would be counterproductive to reach the point where price hikes were resulting in boaters leaving the canals to the point where income would start falling.

But ultimately, Mr Parry feared that pushing the fees up plus finding whatever new funding sources are available “won’t fill the gap”. So what about cutting expenditure? We asked if peripheral activities like – for example – the museums, which are a net drain on resources, might close. Mr Parry’s response was that while everything “will have to justify itself”, there are obligations regarding the historic collection, so they might have to be “creative” as regards bringing in more donations, third party support, and trading.

On the subject of reducing the more central expenditure, we asked if activities such as dredging or lock gate replacement might be hit. Mr Parry said it was possible that both of these could be pared back (and regarding gate replacement, a switch to metal or hybrid gates could save money compared to traditional timber gates), along with other areas such as grouting works and bridge repairs; it was a case of “what can we do to hold back a little” in these areas if it meant that more major projects could still go ahead.

How might closures hit?

So given this limited scope for cost-cutting and raising more income, when exactly will the cash run out and CRT have to start closing canals? Mr Parry couldn’t give an answer – although he made it clear that he thought it was important to flag it up so that people understand that it’s a “very serious risk”. It’s unlikely to be a simple decision that a particular canal is costing more to maintain than can be justified from CRT’s limited income – although when the discussions with Defra began, and there was a suggestion that there might be no money at all post-2027, Mr Parry said that CRT did indeed model some such scenarios.

More likely it will involve a combination of major engineering failures or requirements for large-scale expenditure – particularly on a “not particularly well-used part of the system” where there simply isn’t the money to fund them all, and something will have to give. It might be possible to manage reserves over (say) a three to five-year timescale, but ultimately a situation would be reached where it was no longer possible to keep pushing the date forward and a “difficult choice” would need to be made to abandon one route or another. Otherwise the alternative to closing one canal might be “not looking after any of them very well” compared to today’s standard of maintenance.

In the event that this does happen, Mr Parry made it clear that he saw no wholesale redundancies among staff (and stressed that the trade unions representing CRT employees were very supportive of CRT’s position), although there would be situations where vacancies occurred and were not filled.

Summing up, Mr Parry said that in the meantime this was a “wake up call to not take anything for granted”, that “we will all have to work very hard to keep the network”, that the Trust needed to “be as creative as we can be”, but that there would be “tough choices all the way around”. And that all in all this was a “very shortsighted” way of responding to a report crediting the waterways with bringing in the equivalent of £6 billion a year in benefits to the country.

Frequent towpath mowing is unlikely to be a priority for limited funding

Waterways funding: how did we get here?

Until 2012, the majority of waterways in Britain were run by British Waterways, a public corporation and the successor to the organisation which had been given control of the canals and rivers that were nationalised along with the railways at the start of 1948.

As such, BW’s public funding from Defra was allocated on a yearly basis and had to be spent within the year. In its final ten years this varied between just over £40m and just over £60m per year, covering the waterways in England and Wales (in Scotland they were separately funded through the Scottish Executive). Sometimes the size of the grant wasn’t announced until just weeks before the start of the financial year; on two occasions it was actually cut during the year, with some of the promised cash being clawed back – one of these led to 180 staff redundancies, and to widespread boater protests and campaign events. However, on the plus side there was some acceptance that there would at least be a grant of some kind every year for the foreseeable future, and it was possible to provide extra funding at short notice rather than being locked in to a 10 or 15-year cycle.

In 2012, BW in England and Wales was transformed into the Canal & River Trust charity. The Trustees were initially offered £39m per year for ten years in a public funding contract. They said that this wasn’t enough and they couldn’t take it on; Defra came back with an improved offer, lasting for 15 years. There would be £39m for each of the first three years, then this would rise to £49m, which would be index-linked to rise in line with inflation until 2021-22 (in the event, this saw it climb to £52.6m), following which the funding would remain static for the final five years.

On the plus side, the 15-year contract proofed it against sudden cuts due to short-term economic issues, and allowed the sort of long-term planning that had been impossible in BW days. Unfortunately, the ending of the index-linking in 2022 coincided with the highest inflation for decades, putting CRT finances under serious pressure even before the end of the original 15-year contract. And there was no guarantee of any Defra money at all after 2027 – just that Defra would have to consider whether there was any need for such funding in the future, and announce its conclusions in July 2022. It missed this deadline by a year.

What’s on offer?

The final years of the current contract will see CRT receive £52.6m annually up to 2026-27. In 2027-28, the first year of the new contract, this will fall by 5% to £50m. In each of the subsequent nine years it will fall by the same percentage, meaning that by the final year, 2036-37, it will be down to £31.5m. That’s barely half of what British Waterways received 20 years ago, and that’s without allowing for inflation.

The Defra view: “To date we have awarded CRT £550 million funding and, with this further commitment, are now supporting the Trust with a further total £590 million between now and 2037 – a significant sum of money and a sign of the importance that we place on our inland waterways.”

The CRT view: “From 2027 onwards grant payments decline by 5% each year, with no provision for inflation. This means that the real value of the grant will decline more steeply. This will start from £50 million in 2027/28 and end at £31.5 million in 2036/37 – representing a real-terms reduction of £320 million over the ten years.”

A reminder of the state that the Droitwich was rescued from less than 20 years ago. We don’t want to go back to this…

Public campaigns against cuts launched

The CRT funding announcement has drawn an immediate and forceful response from boating and other user groups, as well as from CRT itself, which has launched a campaign to raise awareness with MPs, the media, and canal supporters everywhere.

Keep Canals Alive: The Canal & River Trust’s campaign urges all those who care about the waterways to support the campaign by writing to their MP demanding that the canals and rivers are properly funded. For its part, the Trust says it will:

– target the media to raise the profile of canals and their importance

– meet with MPs from all parties to influence policy and manifestos

– raise awareness with everyone who lives, works and spends time on our waterways network

– keep collecting and presenting evidence of how valuable canals are for people, wildlife and the economy

– continue to raise vital funds to keep canals open for all to enjoy

To find out more including a link to email your MP and a message from CRT’s Richard Parry, see canalrivertrust.org.ul/keepcanalsalive

Fund Britain’s Waterways: This campaign launched earlier this year in advance of the Defra announcement brings together a large number of waterways organisations led by the Inland Waterways Association, the National Association of Boat Owners, the Royal Yachting Association, the Association of Waterways Cruising Clubs and trade body British Marine, and including dozens of other waterways societies, boat clubs and other groups representing hundreds of thousands of waterways supporters altogether.

The first Fund Britain’s Waterways event is a campaign cruise to Birmingham, planned for 12-13 August. See fundbritainswaterways.org.uk for details of this event and more information about the campaign.

Meanwhile, one organisation which hasn’t joined this campaign is the National Bargee Travellers Association, which has taken a different approach: while it “does not welcome” the Government statement announcing the future funding, it lays the blame on “the Tory Government of 2010-2015 for “deliberately abrogating its responsibility for maintaining vital national infrastructure” by taking the former British Waterways out of public ownership in 2012.

IWA response: The Inland Waterways Association has warned of the potential loss not only of the historic navigable network but of the health, wellbeing, nature conservation benefits, and of thousands of jobs which are dependent on the waterways, if the cuts go ahead.

Recalling IWA’s volunteers stopping the network from being “concreted over in the 1950s” and supporting the restoration and reopening of 500 miles of abandoned canals (with a further 500 potentially restorable), the Association drew attention to the consequences of a reversal of that revival.

National Chair Les Etheridge warned that, coming as they do at a time when the costs of maintaining the system are rising as a result of climate change and inflation pressures, the cuts mean “Our waterways system is in very real danger of disappearing. If parts of the network fall into disrepair or close, this will be at the cost of the hundreds if not thousands of businesses that rely daily on waterways users.”

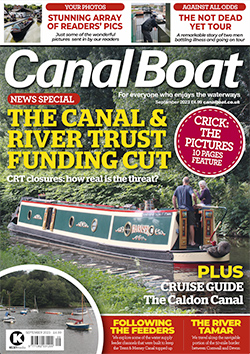

As featured in the September 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the September 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here