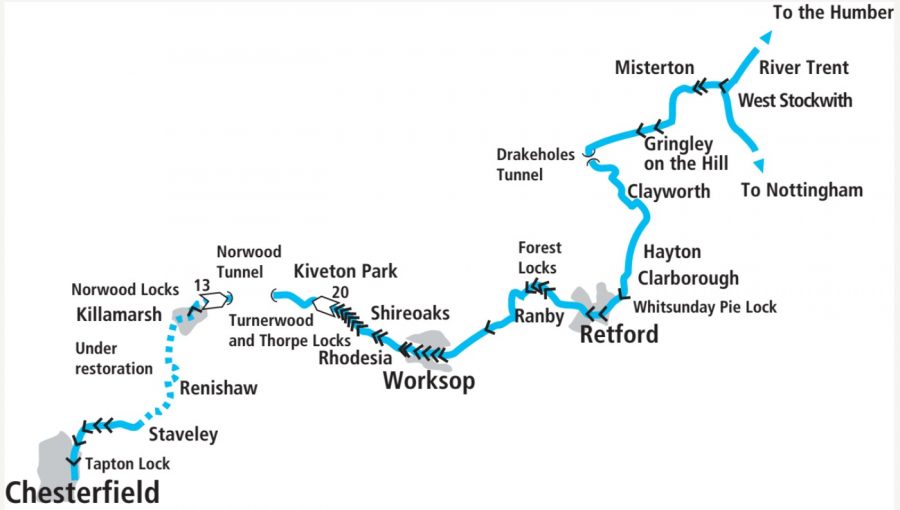

The only narrow canal for miles around, the Chesterfield is rather out on a limb – but its winding route from the Trent to the Peak District’s fringes is well worth visiting for its stunning scenery…

See our guide to the top ten pubs on the Chesterfield Canal here

The Chesterfield Canal is rather out on a limb. In a part of the country where the waterways are mainly river-based, it’s very much an artificial canal. And it’s a narrow-beam one at that, although it’s a long way from the narrowboat’s spiritual home in the West Midlands and surrounding areas: it has the only locks built for 7ft beam craft for quite some distance via any navigable route.

Indeed, for the record, to get to another narrow lock from the Chesterfield you’d need to go down the Trent from the Chesterfield’s entrance basin at West Stockwith to Keadby, up the Stainforth & Keadby Canal, north on the New Junction, up the Aire & Calder, the Calder & Hebble and the Huddersfield Broad Canal to Huddersfield; or alternatively up the Trent from West Stockwith through Nottingham to Trent Lock, then either all the way up the Soar and the Leicester Line to Foxton, or up the Trent & Mersey to Burton.

Getting to the Chesterfield canal

Apart from an excuse for me to indulge myself with some waterways trivia, the above paragraph may give the hint that the Chesterfield is also a little bit ‘out on a limb’ when it comes to the practicalities of getting there from the rest of the canal network. Arriving at West Stockwith involves the River Trent; in particular it involves negotiating the river’s tidal reaches, a trip not to be taken lightly. It should be navigated only in suitably equipped and sufficiently powerful craft, by experienced crews, having consulted tide tables. Lock keepers at tidal locks can provide useful advice. The guide Narrowboat on the Trent is very helpful, as are the Trent charts from The Boating Association and the Chesterfield Canal Trust website – and now there’s a very useful Facebook group dedicated to safe navigation of the tidal Trent called Trentlink – but it’s a private group so you’ll need to join it.

We hope this encourages you to take appropriate precautions rather than putting you off, because this is a canal that’s well worth visiting for its scenery, its heritage, its quietness and remoteness at times, and its contrasts as it climbs from the flat, almost fen-like fringes of the Trent to end at Kiveton in the hills on the edge of the Peak District. And it’s also well worth supporting the efforts that are being made to reopen it right through from Kiveton to the town of its name – but that’s another story, and you can read more recent progress with it in our Restoration Feature.

The basin at West Stockwith, with the tidal lock connecting the canal to the River Trent in the background

West Stockwith to Miserton

It would be a slight exaggeration to describe West Stockwith as “where the canal meets the sea” (in the sense of, say, Glasson Basin on the Lancaster), but there’s a slight hint of that atmosphere in the mixture of narrowboats and cruisers moored around the basin that the entrance lock opens into. There’s a handy pub by the basin to refresh yourself after the tideway trip, and boating facilities, but if it’s shops and other services you need, stay on board as the canal leaves the basin and heads due west for a mile to the larger village of Misterton.

A secluded length near Walkeringham

Here you’ll also meet your first two locks (other than the basin entrance lock from the tideway), and despite what I said about this canal being an oasis of narrowboating in widebeam country, they’re both actually broad beam. That’s something of a historic quirk: as construction of the canal was getting under way in 1772, Retford Corporation and a group of shareholders put up enough extra money to build the first section of the canal wide-beam, so that River Trent barges could work through to Retford. However, despite these two locks and the following three being built to 14ft 6in wide, not all of the bridges were built wide enough, and so the Trent barges never reached Worksop. Still, today it means that two narrowboats can share – although in my experience, meeting another boat isn’t a common occurrence on this quiet canal.

Miserton to Retford

In the typical style of an early ‘contour canal’, the waterway follows the lie of the land as it skirts the northern slope of a gentle hillside, with Gringley on the Hill village just over half a mile away at the top. The route is entirely rural, but an old brickworks chimney poking out of the trees indicates that local industries once made use of the canal. In a dramatic change at Drakeholes the canal takes a right-angle turn to the left, cuts through a spur of the hills in a cutting leading to the short Drakeholes Tunnel, and then turns left again to briefly head back eastwards towards the Trent, before settling down to follow the contours again. The tunnel has no towpath so walkers will need to follow the route over the top; neither does it have much of a portal structure at the south end – just an arch coming to an end, giving it a rather ‘unfinished’ look.

The rather ‘unfinished’ looking Drakeholes Tunnel

Wiseton, Clayworth, Hayton and Clarborough villages (all bar the first of these have pubs) accompany the canal as it winds its way southwards. A line of moored boats at Clayworth marks the home of Retford & Worksop Boat Club, whose involvement in the more recent history of the canal shouldn’t be forgotten: their campaigning and efforts in the 1960s were pivotal in keeping the Stockwith to Worksop length of the canal open when freight traffic had ended, its fortunes were at a low ebb and closure was threatened.

Quiet countryside near Clarborough

The canal finally begins to swing a little more to the west (as if it might just be thinking of heading for Chesterfield after all), as it approaches Retford. The final wide lock (and the first lock for over eight miles), just before the edge of the town, is the celebrated Whitsunday Pie Lock. Sadly the memorable tale of the local farmer’s wife cooking a pie on Whit Sunday for the canal-building navvies to celebrate completing the lock turns out to be a myth (the name ‘Whitsunday Pye’ already existed before the canal was built), but that hasn’t stopped the boat club from marking the date with a boat gathering (with pies) – or, indeed, myself from partaking in appropriate refreshment while on the photo-shoot for this article (albeit I was there on August Bank Holiday, not Whitsun).

An imposing set of red brick warehouses, curving to follow the line of the canal, reminds us that this predominently rural canal was once a busy freight carrier, while on the other side of the bridge the Packet Inn recalls that it didn’t just carry goods – a packet boat once ran passenger services from the surrounding villages to Retford Market.

Approaching Retford Town Lock

Retford Market is still popular today (it operates on Thursdays and Saturdays) and the town’s shops, pubs and other attractions as one of only two towns on the canal make it a good stopping point. In the town is Lock 59 (we’re counting downwards from 65 at the Trent), the first of the narrow-beam locks which are the standard for the rest of the canal. It’s followed by an aqueduct over the River Idle, once itself navigable from the Trent as far as a few miles downstream of here at Bawtry, but which went out of use once trade had begun using the newer canal.

Retford to Worksop

What has up to now been a very gentle climb from the Trent begins to get just a little steeper now, as the canal leaves Retford for quiet open countryside and reaches Forest Locks. A set of four, these are the first real flight of locks we’ve encountered. They’re followed by a particularly winding stretch through Ranby, where the peace and quiet is briefly interrupted by the A1 main road, before the canal follows the little River Ryton towards Worksop.

Climbing the four Forest Locks

The locks continue at intervals, as the canal climbs past Manton, until the 1990s the site of an active colliery now occupied by business parks and reclaimed land, and bends to cross the Ryton on a small aqueduct. Look out for the distinctive Victorian Grade 2 listed Bracebridge Pumping Station building (a long out-of-use sewage pumping station recently reported to have been sold for conversion to new uses) on your left before the canal swings west again to enter Worksop.

The second of the two towns on the navigable part of the canal, Worksop has lost its coalmining and other traditional industries, but still has a market, shops and pubs – and the fascinating Mr Straw’s house, a modest semi-detached house left untouched since the 1920s as the Straw family chose to live without modern gadgets for the following 60 years. For those interested in waterways heritage, it has a very rare example of a former canal warehouse extending on an arch right across the canal – as you cruise under it you can look up and see the hatchway where boats were once loaded. It’s followed closely by Worksop Town Lock, which is so close to Worksop Town Bridge that one of the bottom gate balance beams has had to be cranked to clear the bridge.

The unusual straddle warehouse spans the canal below Worksop Town Lock

Worksop to Shireoaks

For many years the next lock, Morse Lock, was the limit of navigation: Norwood Tunnel had collapsed in 1907, and the lengths either side of it to Chesterfield on the west and Worksop on the east had fallen derelict. But following campaigning by Chesterfield Canal Trust and funding grants from the EU and UK Government, the canal was reopened in 2002 from Morse Lock to Norwood Tunnel. These extra six miles extended the total navigable length to 32 miles – but they also provided a contrasting section with a completely different character from the wandering, gently climbing 26 miles we’ve travelled from West Stockwith.

The canal now makes a bee-line for the hills, with Morse Lock followed shortly by Stret Lock and Deep Lock. Two more locks see the outskirts of Worksop left behind as the canal passes Rhodesia village, then a flight of three leads to Shireoaks. Look out in the marina basin on your right for a possible glimpse of Dawn Rose – a faithful re-creation of the canal’s distinctive original ‘cuckoo boats’ (being so far from other narrow canals, it’s not surprising that the Chesterfield developed its own characteristic style of working boat) which has been built by a group within Chesterfield Canal Trust using traditional methods and materials as a heritage and educational resource.

Thorpe and Turnerwood locks climb through beautifully secluded countryside to the canal’s summit level

Shireoaks to Kiveton

And now the climbing really begins in earnest. Boundary Lock, a new lock added to overcome the effects of coal mining subsidence during the canal’s closure, marks the start of one of the steepest climbs anywhere on the waterways network – at least when measured in numbers of locks, with the final 20 crammed into a single mile. It’s achieved by using multiple staircase locks – two pairs and two triples – but a curious feature is that the individual chambers are unusually shallow, averaging only a little over 4ft rise.

But never mind the statistics, the Turnerwood and Thorpe lock form a magical flight, climbing through beautiful secluded countryside with few roads nearby, and just the odd rumble of a train passing on a nearby line. And on finally leaving the last lock behind, the summit level is even quieter.

But as so often, and just like the brickworks chimney we saw right back at the start, there’s a clue that this wasn’t always idyllic countryside in the shape of a former wharf and an interpretation sign which explains that this was where the stone from a nearby quarry was loaded in the 1840s for building the Houses of Parliament.

On the summit level: a quiet length of canal today, but once a busy wharf where stone for the Houses of Parliament was loaded

A narrow, steep sided and increasingly deep cutting leads to a bridge at Kiveton Park, carrying the first public road since Shireoaks and providing convenient access to Kiveton Park station and adjacent pub. Beyond the bridge, a winding hole enables boats to turn round, as in just a few more yards the canal reaches its terminus – at least for now.

The 2893-yard Norwood Tunnel has suffered major damage from coal mining, will need to be completely rebuilt (and partly bypassed), and then there are 13 more staircase locks to restore, and other challenges for the Canal Trust and partners to overcome on their way to bringing the boats back to Chesterfield.

Kiveton is a great place to tie up on a quiet mooring and dream of a future cruise along these western lengths – but if you’re feeling energetic you can already walk them today.

Approaching the current limit of navigation at Kiveton

Image(s) provided by:

Martin Ludgate