As Herefordshire & Gloucestershire Canal Trust’s volunteers begin digging a brand new length of canal, Martin Ludgate reviews progress along the whole route

Sometimes it can be encouraging when planning these articles to look back at the last time we featured the same canal. It’s great to see the optimistic ideas of a few years ago turning into real progress on the ground. And to see their place being taken projects which weren’t even on the radar when we last looked.

On the other hand, it can in other cases be deeply depressing how little things have moved forward, thanks often to circumstances completely beyond the control of the restoration groups.

And just occasionally, we find they’ve moved on in completely different directions to what we might have expected when we last looked.

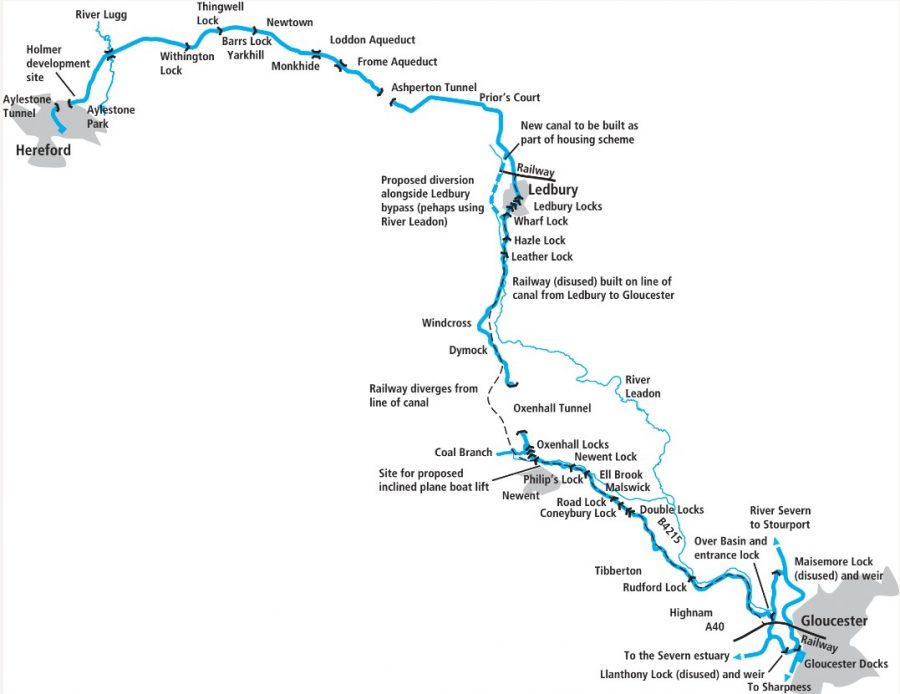

In the case of restoring the Herefordshire & Gloucestershire Canal, a long-term project with a 34-mile route abandoned since the 1870s that’s set to occupy the Herefordshire & Gloucestershire Canal Trust for quite some time to come, I think it’s fair to say that it’s a bit of all three. So rather than get daunted by the challenges to overcome before boats from the Severn are cruising from Gloucester through Newent and Ledbury to Hereford, let’s start with an example of my first case above: yesterday’s dream turning into tomorrow’s reality.

The dotted line shows where the new length of canal is being built

Digging deep at Malswick

Last time we featured the canal, the section at Malswick hardly got a mention. It was part of the Gloucester to Newent section, most of which was used in the 1880s as the route for a railway line (in turn abandoned in the 1960s). As such there were few surviving canal structures between the extremities of this section where the railway deviated from the canal at Over and north of Newent. And so it hadn’t received much attention in the early years of restoration, when the Trust had concentrated on more achievable projects in areas unaffected by the railway such as Monkhide and Oxenhall.

But all that changed in November2021 when H&GCT gained planning permission to reinstate a length of canal at Malswick. And not just a derelict section of canal being restored but in effect a brand new length. The former railway embankment occupies the approximate route of the original canal, and removing the embankment isn’t practicable, so a new channel is to be built alongside.

In the context of the complete restoration its length is a modest 600m. But it’s highly significant as it’s an important first step towards reinstating the railway-affected lengths. Before the permission could be granted there had to be a fair amount of the sort of preparation that the original canal builders didn’t need to worry about: a bat survey, a newt survey, a slow-worm survey, an archaeological investigation… altogether over 100 documents accompanied the application. But in the meantime, preparatory work got under way to clear the site, and to build stream culverts to provide continued farm access to the land after the canal has been built across it.

Recently built culvert as part of the plans for Malswick

Now that the go-ahead has been given, the major earth-moving effort to create the new canal is set to get underway this summer, and national volunteering body the Waterway Recovery Group will be supporting the Trust’s own team with several whole weeks of its programme of Canal Camps. And it won’t just be about actual ‘canal digging’ – there will also be culverts to be built to carry two streams under the canal.

The Trust is optimistic that the channel will hold water without the need for lining beyond the natural clay that’s available on site (it’s actually a myth that all canals were lined with puddled clay to make them watertight- many ran through non-porous ground and didn’t need clay). In that case it’s hoped to have the canal in water by 2023.

It’s likely to be some time before it sees its first narrowboat, but in the meantime H&GCT hopes that the new length will get plenty of use. With a fully accessible towpath on one side, a separate path with hedge on the other side (1,000 hedge plants and trees have been donated), and a slipway and small car park off the main B4215, the Trust is hopeful that the site will become a local attraction popular with walkers, canoeists and paddleboarders. And one day it will be part of a restored canal.

Opportunities in Hereford

But let’s turn now to a length where the last few years have been more of a frustrating time. And by contrast to the Malswick site it’s on the Ledbury to Hereford section, whose route wasn’t used to build a railway line after it closed, and which you might have thought would be easier to restore. But that’s not the always case: towards the western end, as it enters Hereford, more of the canal has been obstructed since it was abandoned. Seven years ago in 2015 the planned Holmer residential development in a former industrial area to the north east of the town provided a great opportunity to reinstate a 370m length of canal. This is where the canal used to run in a cutting 7-8m deep, but which had been filled in with industrial waste from an old tile works. Planning permission for the housing scheme committed the developer to re-excavating the canal cutting.

Again, 370m might not sound like much, but was a tricky length and also an important link in a restorable section leading from the countryside into the town. To the east, Aylestone Park has been created over the last 15 years with the restored canal as an important feature, and is followed by the reinstated Roman Road bridge carrying the canal under the A4103 and into the country. Meanwhile to the west, the canal plunges into the short Aylestone Tunnel (which conveniently takes it under the main railway line – meaning that Network Rail inspects the canal tunnel regularly!) following which the route into town passes through a series of completed or planned development sites.

First is a retail park completed some years ago incorporating a length of canal and bridge. Next is The Tudors, another housing development site (providing another opportunity to reinstate the canal), then a length of canal owned by the Trust. Finally a former steel stockholder site earmarked for replacing with student accommodation (once again giving a chance to include a route for the canal), occupies the approach to the site of the terminus.

New canal bridge built as part of retail park in Hereford

None of these potentially helpful developments are certain. And there are other issues such as a sewer buried under the canal bed, to which the water authority will need to retain some kind of access. But there’s a route available, there’s the opportunity to put back the towpath as a first step (which would protect the line, and which the local authority is keen on as a ‘green corridor’), and in 2015 the Holmer development looked set to get things under way.

But then a year later, the developer applied for permission to drop the canal reinstatement from the scheme. In the end, the housing scheme didn’t happen. Another three years on, a new developer took up the reins with a new plan for affordable kit-built homes – but without the cash available for canal reinstatement. However, while it may seem on the face of it like the restoration has gone nowhere in seven years, at least the land will be made available to the Trust, the protected route into the town remains intact, and further developments should bring about some real restoration progress in the future.

A new route round Ledbury?

Meanwhile some miles east of Hereford at Ledbury, once again there might not seem to have been much (if any) movement on the ground, but in planning terms there are signs that things are happening. And again it’s a housing development which it’s hoped will provide the means to reopen the canal. But first a little background to the canal in Ledbury…

Historically the canal ran through the middle of Ledbury, climbing a flight of locks through the town. But this section was obliterated by the Gloucester to Ledbury railway, parts of the railway were built on after it closed, and restoration on the original route is seen as impracticable. It would be much more straightforward to create a new route which follows the River Leadon as it skirts the west side of Ledbury alongside the town’s bypass road. This has long been the Trust’s preferred route for reopening the canal.

North of Ledbury, the Leadon passes under a viaduct carrying another railway line. From here northwards the restored canal would cut across the fields before passing through a new bridge under the B4214 to regain its original route. This area is where housing developers are planning to build 625 houses. As part of the planning agreement achieved in 2021, they will pay £1m in what’s known as a ‘Section 106’ agreement to create the new length of canal (which will include new locks to replace those in Ledbury).

It isn’t quite as simple as that (is it ever?) There are complex negotiations between the Trust (who feel that the 675m of canal would be best built as a single job) and the developers who aren’t experienced in building waterways and (not surprisingly) are most interested in building the housing. But again, if all goes well, it could form a key link in a length of restored canal. To the west, there are 12 lock-free miles of summit level, with sections already restored at Monkhide and Kymin, plus a long section through Ashperton Tunnel that’s intact, in water, and accessible as an attractive walk. Clearly this section has good prospects for further reopenings.

And to the south, subject to negotiations with the Environment Agency, it should be possible to canalise the Leadon to provide a restored route around Ledbury, complete with moorings for the town.

At this point I sense the usual questions from canal boat owners reading this article, who will understandably be frustrated to read that (like many canals under restoration) it seems that whilst there’s plenty going on, there isn’t much prospect of linking it to the national network and welcoming visiting boaters (unless they have trailboats or other portable craft) for quite some years.

But fear not: in my opening remarks I said that occasionally we find that canal restorations have moved on incompletely different directions to what we might have expected. I’ll finish with a couple of examples of this…

A link to the network?

At Over, where the canal met the River Severn on the outskirts of Gloucester, the original entrance basin was rebuilt during a mammoth volunteering effort against tight deadlines (under a planning agreement) by WRG and HGCT volunteers in 1999-2000. And in 2012, volunteers returned to create the Vineyard Hill length, an extension of the basin to form the start of the route towards Hereford. But there’s been no further extension since then, and no work to restore the entrance lock to link it to the river. However that might change.

Over Basin, rebuilt by volunteers

H&GCT recently engaged the services of one of the Inland Waterways Association’s Restoration Hub’s honorary consulting engineers to look at options for linking the canal to the river, and discuss them with H&GCT – because it’s not a straightforward job.

Upstream of Gloucester the River Severn splits into two channels: the Eastern Channel (which boats coming down the river from Worcester and Tewkesbury use to get to Gloucester Docks) and the (not normally navigated) Western Channel – which the H&G Canal meets via a very deep lock at Over. These two channels then join together downstream of the city.

But to complicate matters, there are weirs on each of these channels (at Maisemore on the Western Channel and Llanthony on the Eastern Channel) where the river becomes tidal – and the Severn is famous for its huge tidal range, fast currents, and tidal bore. So to get from the canal to the non-tidal river and Gloucester, either boats would need to wait for a suitable high tide to make a level at one or other of these weirs, or one of the locks which once accompanied the locks would need to be restored – which would be difficult.

The IWA engineer came up with three options. The first would be basically to keep the current situation, restore the entrance lock, reinstate one of the locks by the weirs, and accept that it wouldn’t be an easy journey because of the tidal length.

The second option would involve digging a new cut across the ‘island’ formed by the two channels (meeting the Eastern Channel near the entrance lock to Gloucester Docks) with a new tidal lock to access it from the Over end. But this, like the first option, would involve restoring the Over Basin entrance lock- which at (possibly) around 30ft deep to cope with the tides, isn’t an easy job.

That leads to the third option: a new aqueduct over the Western Channel at Over, leading into a new non-tidal cut across the ‘island’. It may sound far-fetched, but H&GCT described it as a “useful session” with the engineer.

New thinking at Newent

And finally, when it comes to restorations moving in unexpected directions, there are the plans for Newent. Here, a section was restored some years ago from the portal of Oxenhall Tunnel southwards, including restoring House Lock and Ell Brook Aqueduct, to reach the point where the canal disappears under the old railway route on the site of the former Newent Station.

The restored House Lock at Oxenhall

Last time we reported from here, the plan was to reinstate the canal along the railway route, using the station platforms as moorings, and the abutments of the railway bridge over the B4215 to support a new aqueduct. It sounded interesting and could be quite an attraction. However the downside was that the levels would be difficult – the canal originally went under the road here – and there would be new locks needed, water supply issues, and perhaps problems with waterproofing the canal on a high embankment. So the Trust has had a rethink…

The proposal now – and it was a model of this which first caught my eye when I saw it at the 2021 IWA Festival of Water, and which prompted me to discuss the H&GCT’s plans – is for an inclined plane boat lift to take boats up a slope, over the bridge, through the old station, and back down to canal level on the other side. But not just any inclined plane.

They’re talking about a ‘dry’ incline with trolleys rather than tanks, rather like the ones used at some boatyard slipways. And they aren’t wedded to the idea of it running on rails or using cables. It could be a tractor towing a boat-carrying trailer up a concrete ramp, shunting around it at the top, and backing it down into the canal on the other side.

That may also sound far-fetched. But it’s really no different from what happens at boatyard slipways every day.

However the principle of getting some restoration work going on the Gloucester to Newent section is less of an exotic idea. The Trust is looking at options for extending the Vineyard Hill site from Over Basin northwards; further on between there and Malswick is a possible solar farm site which could see another section restored, nibbling away at the gaps in the restoration. And that brings us back to where we started at Malswick, where work starts this year on building the first section of new canal – and WRG’s volunteers are looking forward to getting stuck in in just a few weeks’ time.

To find out more about the Herefordshire & Gloucestershire Canal and to support the Trust’s plans for restoration, see their website.

The Herefordshire & Gloucestershire Canal: a brief history

The Herefordshire & Gloucestershire Canal was a product of the ‘Canal Mania’ of the early 1790s, when the financial success of the early canals which had opened in the previous 20 years led to a widespread belief that canals were a ‘magic money tree’, and to many people putting good money into buying shares in some really not very promising canal schemes. In the case of the H&G, they were investing in a 34-mile route which passed through no major towns in between its termini at Hereford and Gloucester – just a couple of small market towns (Ledbury and Newent) and a number of villages.

It wouldn’t have been a very profitable canal at best, but its fortunes took a nosedive when the proprietors chose to modify the route so that it would serve a small coalfield developing in the Newent area. Unfortunately this meant adding the long, expensive and difficult to construct Oxenhall Tunnel to the canal – and in the end, the coal turned out to be very inferior. The tunnel was eventually finished, and in 1798 the canal was completed from Gloucester as far as Ledbury – but all the money for the entire route had been spent.

It carried a modest local trade; however it might never have got any nearer to Hereford had it not been for the arrival 30 years later of adynamic young engineer called Stephen Ballard. Convinced that completing the canal would turn its finances around, he set about raising the funds to extend it to Hereford. Unfortunately by the time it arrived there in 1845 the canal age was drawing to a close, it was the time of the ‘Railway Mania’, and the canal company was in debt with no great hope of better times ahead.

No sooner had the canal opened than the company was considering selling out to a railway company to use its route to build a new line. In the end, the canal survived for another 35 years before it was sold to the Great Western Railway. It closed in 1880, and parts of the length from Gloucester to Ledbury were used for a railway, while the remainder was left to decay. The railway in turn closed to passengers in 1959, although part of it survived for freight traffic for another five years.