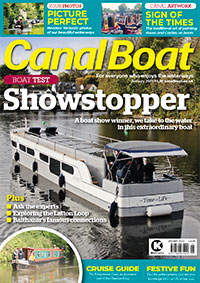

A pioneer dating from the early days of the industrial waterway building era, the Bridgewater Canal later became a key link in North West England’s network – and a crucial part of the popular Cheshire Ring cruising circuit today.

Words and Pictures by Martin Ludgate

Today, the Bridgewater Canal forms an important part of the Cheshire Ring, a 100-mile circuit of waterways which not only encircles a large part of Cheshire, but takes in a trip through central Manchester and dips its toe into Staffordshire. At the same time, via its Stretford and Leigh Branch the Bridgewater also provides the North West’s link to the Leeds & Liverpool and Lancaster canals.

And yet when it opened its original main line in the 1760s, all of these connections were in the future. The pioneering Bridgewater Canal, while not actually the earliest in the country (there are several earlier ones, from the Sankey Canal right back to the Roman-built Fossdyke Navigation) stood alone. Built to serve a local need by delivering coal from the Duke of Bridgewater’s mines at Worsley to the city of Manchester, the canal had no connections to any other waterway.

That it later gained so many links as the network grew is perhaps testimony to its success and the role it played in kickstarting the canal era. Not to mention the political astuteness of the ‘Canal Duke’ when it came to supporting, opposing or influencing the various plans for other canals to the advantage of his own waterway.

The route from Worsley to Manchester tends to get regarded as a branch these days, with the Bridgewater’s later extension running southwestwards from a junction at Trafford down to Preston Brook and Runcorn seen as the main line. But as the Worsley-Manchester line was the original one that set the ball rolling, we’ll follow it first. Unlike the former coal trade, which ran from west to east, we’ll head westwards, starting at the eastern end in central Manchester.

The canal makes its way out of Manchester surrounded by old and new buildings

JOINING THE CANAL

It’s where many visiting boaters join the Bridgewater Canal today; in particular those who are cruising the Cheshire Ring in an anticlockwise direction, or those who’ve crossed the Pennines via the Rochdale or Huddersfield canals. All of these routes converge on the ‘Rochdale Nine’, the Rochdale Canal’s sequence of nine locks descending through the city centre and culminating in Duke’s Lock 92, which leads out into the start of the Bridgewater at Castlefield Basin.

Despite the name, Castlefield isn’t just one basin. It’s a whole complex, with multiple arms, wharves and basins incorporating a length of the River Medlock, surrounded by assorted old buildings including the historic Grocer’s Warehouse, and crossed by multiple high-level railway viaducts and a striking modern footbridge. In 1766 it was described as “a sort of Maritime Town, or Dutch Seaport”. In the last 40 years it’s gone from being a run-down inner-city industrial area to a lively and popular part of the city with restaurants and bars, and it’s a great place to tie up to visit Manchester.

From here the Bridgewater Canal strikes out westward surrounded by old industrial buildings, modern developments and railway lines. Look out for a canal arm leading off on the right: until the 1990s the Hulme Lock Branch formed a connection to the River Irwell and so to the Manchester Ship Canal, but problems with stability of the lock led to it being abandoned in favour of a new connection which we will pass shortly.

As the city centre is left behind and the canal approaches Old Trafford, it passes what was once an industrial area surrounding the Ship Canal’s Pomona Docks, but is now largely empty land and earmarked for a massive £1bn residential development scheme. All bar one of the docks have been filled in; the survivor owes its secure survival to the fact that it was connected to the Bridgewater Canal by the new Pomona Lock in the 1990s, as a replacement for the closed Hulme Lock (see above).

TRAFFORD PARK

To our right there are glimpses of the Ship Canal itself and the new developments that have already taken place as part of the Salford Quays regeneration, while on our left the canal passes close to the famous Manchester United football stadium – while for those who prefer cricket, the Lancashire County ground isn’t far away.

In the Duke of Bridgewater’s day, Trafford Park was a “beautifully timbered deer park”. However, thanks to the industrialisation, helped on its way by his canal (and particularly by the later arrival of the Manchester Ship Canal), it became the first planned industrial estate in the world. At its peak in the mid-20th century it was the largest in Europe, employing 75,000 people, and ran its own internal railway network. Since then it’s seen a decline, a revival of fortunes with modern technological industries and the arrival of the Trafford Centre – at its opening, the country’s biggest shopping centre. The canal skirts the south side of the industrial area to reach a junction known as Waters Meeting.

Here we’ll take the right fork, cutting through Trafford Park on a bold, straight, wide embankment: this might be an early canal, but has nothing of the tortuous windings and avoidance of earthworks which were a feature of many of the waterways which immediately followed it. Given that the same engineer – the famous James Brindley – was involved in almost all of them, this may seem surprising. Some have suggested that the Duke himself, or his agent John Gilbert, could have had more of an involvement in the decision-making than Brindley. Others have pointed to (possibly exaggerated) reports that its construction came close to bankrupting the Duke, and concluded that perhaps the need for more careful control of canal engineering costs was what we’d call a ‘learning point’ today. I’ll leave it to the waterways historians to decide!

A rare sight nowadays: Barton Swing Aqueduct opens to allow a ship to pass on the Ship Canal

REMARKABLE AQUEDUCTS

The embankment leads to Barton upon Irwell, and to one of the great engineering feats of our canal system – Barton Swing Aqueduct. This doesn’t go back to the Duke’s day, but it’s a later part of a story that began then…

We’ve mentioned that the Duke built the canal to take his Worsley coal to Manchester, but there was more to it than that. There was already a waterway serving the city, the Mersey & Irwell Navigation, a river-based route which took barges from the Mersey estuary up to Manchester. However rather than simply building a canal to connect his mines to the River Irwell, he chose (there’s an unconfirmed story that this was as a result of the Mersey & Irwell refusing to agree a sensible toll rate with him) to build an independent canal – and to get it to Manchester he would have to cross the Irwell. This meant building an aqueduct with arches high and wide enough to allow barges on the river to pass under it, which was something that hadn’t been attempted before in this country.

The resulting structure was quite a wonder, as a local poet put it… “…Seen and acknowledg’d by astonish’d crowds, From underground emerging to the clouds; Vessels o’er vessels, water under water…”

Once again it was rather a contrast to many of the aqueducts which immediately followed it, and which tended to consist of a heavily built embankment, pierced by a series of relatively small culvert arches to carry the river – although in fairness, none of them had to carry barges underneath.

Sadly this fine pioneering aqueduct is no more: when the Manchester Ship Canal was created along the approximate route of the earlier Mersey & Irwell Navigation, a new structure was needed which would allow late 19th century ships to pass. The result was the even more remarkable Barton Swing Aqueduct, unique in the world.

Mounted on a pivot set on an island in the middle of the ship canal, the entire structure swings through 90 degrees to allow shipping to pass, with guillotine lock gates closing off the water at both ends of the swinging span, and at the ends of the approach channels on each side. Ships aren’t particularly common on the upper reaches of the canal these days so you’re unlikely to have to wait for it to be swung back – but if you do, it’s worth the wait just to see it in action.

Where it began: Worsley Packet House, close to where the Duke’s mines were

THE DUKE’S MINES

Another industrial length leads from Barton to Worsley, and you’ll probably notice a change in the canal’s water, which has acquired a distinctive orange tint. This is due to ochre, an ore of iron, which is present in the water that drains into the canal from the Duke of Bridgewater’s mines at Worsley – and that’s a clue to another remarkable feature that’s approaching.

Rather than the coal being hauled out of the mine on wagons pulled by pit-ponies, or raised up a shaft by a hoist, it was taken out directly in boats which worked through from navigable mine tunnels, emerging onto the canal at Worsley Delph. It developed into an extensive system, and we cover its history in our Cruise Guide Extra on page 54. You’ll see the arm leading off to Worsley Delph to the right, as the main canal bears left, with the fine black and white half-timbered Packet House directly ahead. This is a 19th century replacement of an earlier building where Packet Boats (passenger boats) once operated a service to Manchester.

Although serving the mines was the main purpose of the canal, it continues beyond Worsley and forms a useful connection. Leading through the first actual countryside that we’ve seen on our journey, the canal heads westward. The Astley Green Pit Museum reminds us that there was industry here too, then a couple more rural miles bring us to Leigh. A former cotton mill town, it’s a useful stopping place with shops and waterside pubs – and it’s where the Bridgewater Canal ends and the Leeds & Liverpool’s Leigh Arm begins, almost unnoticed.

Almost, but not quite: there’s a sign to mark the fact that you’re now re-entering Canal & River Trust territory (see Boater’s Notes), and a small hand crane. These are a Bridgewater Canal feature and were (and in some cases still are) used to lift in the stop-planks which are used to dam off sections of canal for repairs. This set mark the end of the Bridgewater Canal.

Striking modern buildings on the edge of Altrincham

MAIN LINE

Let’s now return to Waters Meeting, and take the route heading southwestwards. This was begun even as the Worsley to Manchester section was being built, and was intended to link the canal to the Mersey estuary. And if the story about the Duke’s dispute with the Mersey & Irwell Navigation over tolls (see above) was apocryphal, his disagreement with them over his plan to bypass their entire route by building his own line to the Mersey certainly wasn’t. But despite their opposition he got his Act of Parliament, and opened what we now regard as the canal’s main line.

A long, straight but not unattractive stretch through the south west Manchester suburbs is interrupted briefly by a small aqueduct over the River Mersey – and a pub with a floating terrace in Sale. Skirting the fringes of Altrincham and passing some striking modern developments (and some old factories including the Linotype works undergoing redevelopment for new uses), the canal finally leaves the urban area for the Cheshire countryside. The canal’s characteristically bold construction methods continue, with many local roads (and the River Bollin) spanned by aqueducts. Lymm is an attractive small town, and is followed by Grappenhall. And although the canal follows the southern outskirts of Warrington for several miles it’s a pleasant length and manages to retain a rural outlook on the south side for much of the way.

The countryside returns as the canal passes Walton and Moore to reach Daresbury, notable for a large science park alongside the canal, and also for being the birthplace of Lewis Carroll – he’s commemorated by a window in the church. A final length of canal leads to Preston Brook, and to another junction – where once again, what was once seen as the canal’s main line is regarded today as a five-mile branch.

On the five-mile cul-de-sac from Preston Brook to Runcorn

MAKING CONNECTIONS

Most boaters who have cruised down from Manchester will be heading for the Trent & Mersey Canal, which continues the Cheshire Ring route southwards as well as providing connections to the Shropshire Union Canal and the Midlands. And if you carry straight on at Preston Brook junction, then after just a few hundred yards (and once again with a sixgn to mark your return to Canal & River Trust territory) you’ll find yourself on the start of the Trent & Mersey as you approach Preston Brook Tunnel. But although linking his canal to the T&M was high on the Duke’s priorities, the primary aim of the canal we’ve been following from Trafford was to connect to the Mersey. And to follow what’s left of that route, we turn sharp right at Preston Brook Junction.

As we’ve mentioned several times, the canal has followed a bold, straightish course for much of its route. But now, for just about the first time, it begins to meander a little more as it enters slightly more hilly ground heading westwards. We’re skirting the north edge of the Runcorn built-up area, but this isn’t at all obvious for the first two or three miles. It finally starts to get more industrial and a main road accompanies the canal on the approach to the Runcorn terminus.

Terminus? Yes, that’s right: sadly the canal no longer provides a link to the Mersey Estuary (or to its replacement as a navigable route to Liverpool, the Manchester Ship Canal), the connecting flights of locks having been abandoned as recently as the 1960s – depriving the Bridgewater of the only locks on either of its main routes. Yes, that’s another perhaps surprising feature for such an early canal – the engineers managed to build almost all of it on a single level with the locks all grouped together in one place.

But where they once descended towards Runcorn Docks, the canal now comes to a dead stop at the three-arch Waterloo Bridge. Immediately beyond there, it was blocked by slip-roads built as part of alterations to the approaches to the 1960s Runcorn-Widnes road bridge. But just recently, with the opening of the new Mersey Gateway bridge, and the older bridge being reduced to a local function, the slip-roads have been removed. This represents a golden opportunity for restoring and reopening the old canal route, creating a link not just to the Ship Canal but to the underused River Weaver. The Runcorn Locks Restoration Society is on the case!

But until then, cruise the ‘Runcorn Arm’ as a pleasant five-mile detour from the Cheshire Ring, and a historic part of the main line of a pioneering canal.

BOATERS’ NOTES: The Bridgewater Canal is not part of the Canal & River Trust system, it is operated by the Bridgewater Canal Company, a part of the Peel Group which also owns the Manchester Ship Canal. Under a reciprocal agreement CRT licence holders visiting the Bridgewater Canal may remain on the canal without payment for periods not exceeding seven consecutive days. Any craft staying longer than this will need a temporary short term Bridgewater Canal Licence at a cost of £40 for seven consecutive days – contact 0161 629 8266. Pomona Lock provides access from the Bridgewater Canal to the Manchester Ship Canal, which can be used as a through route to the Weaver, the Shropshire Union Canal or the Mersey estuary. However, those planning to use this link should note that it will need to be booked in advance, and that the Ship Canal’s operators have a number of requirements for leisure boats including a certificate of seaworthiness from an approved surveyor and copies of the appropriate bylaws and transit notes. Some of the requirements are relaxed for boats only visiting the ‘upper reaches’ at the Manchester end – Salford Quays, the River Irwell and the Ship Canal above the top lock at Mode Wheel.

As featured in the January 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here

As featured in the January 2023 issue of Canal Boat. Buy the issue here